Difference between revisions of "Taï National Park"

| (21 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | [[West Africa]] > [[Côte d'Ivoire]] > [[Taï National Park]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[West Africa]] > [[Côte | ||

| − | [[ | + | '''[https://wiki-iucnapesportal-org.translate.goog/index.php/Taï_National_Park?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=fr&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp Français]''' | '''[https://wiki-iucnapesportal-org.translate.goog/index.php/Taï_National_Park?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=pt&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp Português]''' | '''[https://wiki-iucnapesportal-org.translate.goog/index.php/Taï_National_Park?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=es&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp Español]''' | '''[https://wiki-iucnapesportal-org.translate.goog/index.php/Taï_National_Park?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=id&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp Bahasa Indonesia]''' | '''[https://wiki-iucnapesportal-org.translate.goog/index.php/Taï_National_Park?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=ms&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp Melayu]''' |

| − | = Summary = | + | __TOC__ |

| + | = Summary = | ||

| − | * Western chimpanzees ( | + | <div style="float: right">{{#display_map: height=190px | width=300px | scrollzoom=off | zoom=5 | layers= OpenStreetMap, OpenTopoMap|5.77, -7.12~[[Taï National Park]]~'Pan troglodytes verus''}}</div> |

| − | * It has been estimated that 406 (CI: 265-623) individuals occur at the site. | + | * Western chimpanzees (''Pan troglodytes verus'') are present in Taï National Park. |

| − | * The chimpanzee population trend is stable. | + | * It has been estimated that 406 (CI: 265-623) individuals occur at the site. |

| + | * The chimpanzee population trend is stable. | ||

* This site has a total size of 5,0812 km². | * This site has a total size of 5,0812 km². | ||

| − | * Key threats to chimpanzees are poaching and diseases. | + | * Key threats to chimpanzees are poaching and diseases. |

| − | * A range of | + | * A range of conservation activities are implemented, including permanent presence of researchers and tourists, anti-poaching patrols, environmental education and measures to prevent disease transmission to chimpanzees. |

| − | * Taï National Park is the largest remaining forest block in the Upper Guinea Region and is home to one of the longest-running chimpanzee research sites. | + | * Taï National Park is the largest remaining forest block in the Upper Guinea Region and is home to one of the longest-running chimpanzee research sites. |

| − | |||

| − | Taï National Park ( | + | [[File: CIV_Tai_chimpanzee_Sonja_Metzger_WCF.jpg | 400px | thumb| right | Chimpanzees, Taï National Park (Côte d’Ivoire) © Sonja Metzger/WCF]] |

| − | + | = Site characteristics = | |

| + | Taï National Park (IUCN category: II) was created in 1972 and proclaimed a UNESCO world heritage site in 1982 (Criteria iii, iv, [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/195 UNESCO 2019a]). The park is located in south-western Côte d'Ivoire (5°15'-6°07'N, 7°25'-7°54'W), approximately 200 km south of Man and 100 km from the coast. With a size of 5,0812 km², it is the largest protected forest block in Côte d’Ivoire and one of the last tropical lowland forests in the Upper Guinea Region. The topography is mostly flat, but some Inselbergs occur. The majority of the forest in the park has never been logged and this mature, old-growth forest supports a rich diversity of species. It has been estimated that around 1,300 plant species occur in the park, 80-150 are endemic to the Upper Guinea region (BirdLife International 2019). Because of its diversity of bird species, notably white-breasted guinea fowl (''Agelastes meleagrides'') and large hornbill species, it is considered an Important Bird Area (BirdLife International 2019). Primate species recorded in the park include olive colobus (''Procolobus verus''), western red colobus (''Piliocolobus badius''), king colobus (''Colobus polykomos''), and Diana monkey (''Cercopithecus diana''). Other mammal species include the Pel's flying squirrel (''Anomalurus peli''), forest elephant (''Loxodonta africana ''), pygmy hippopotamus (''Choeropsis liberiensis''), Water chevrotain (''Hyemoschus aquaticus''), African buffalo (''Syncerus caffer''), and a range of duikers, including Maxwell's duiker (''Philantomba maxwellii''), black duiker (''Cephalophus niger''), zebra duiker (''Cephalophus zebra''), and Jentink's duiker (''Cephalophus jentinki''). Reptile species include (''Crocodylus cataphractus'') and African dwarf crocodile (''Osteolaemus tetraspis''), Home's hinge-back tortoise (''Kinixys homeana''). | ||

| − | + | '''Table 1. Basic site information for Taï National Park''' | |

| − | '''Table 1 | + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="Site_characteristics-table" |

| − | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class=" | + | |Species |

| − | | Area | + | |'Pan troglodytes verus'' |

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Area | ||

|5,0812 km² | |5,0812 km² | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Coordinates | + | |Coordinates |

| − | |5.77 | + | |Lat: 5.77 , Lon: -7.12 |

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Type of site | ||

| + | |Protected area (National Park) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |Habitat types |

| − | | | + | |Subtropical/tropical moist lowland forest, Agricultural land |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |Type of governance |

| − | | | + | | |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/habitat-classification-scheme IUCN habitat categories] [[Site designations]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | = Ape status = | |

| + | Since 2005 annual surveys on western chimpanzees have been implemented by OIPR and the [https://www.wildchimps.org/index.html Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (WCF)]. Estimated chimpanzee abundance ranges between 300-800 individuals and the population seems to be stable (Campbell et al. 2008). Since 2016, the WCF has used camera traps to systematically monitor biodiversity in 200 km² in the Taï National Park (Cappelle et al. 2019). | ||

| − | '''Table 2 | + | '''Table 2. Ape population estimates reported for Taï National Park''' |

| − | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class=" | + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="Ape_status-table" |

| − | ! Species | + | !Species |

| − | ! Year | + | !Year |

| − | ! | + | !Occurrence |

| − | ! | + | !Encounter or vistation rate (nests/km; ind/day) |

| − | ! | + | !Density estimate [ind./ km²] (95% CI) |

| − | ! | + | !Abundance estimate (95% CI) |

| − | ! | + | !Survey area |

| − | ! Source | + | !Sampling method |

| − | ! Comments | + | !Analytical framework |

| − | ! A.P.E.S. database ID | + | !Source |

| + | !Comments | ||

| + | !A.P.E.S. database ID | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2016 | + | |2016 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.07 (0.05-0.11) | + | |0.265 |

| − | | | + | |0.07 (0.05-0.11) |

| − | |entire | + | |406 (265-623) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| − | |Tiédoué et al. 2016 | + | |Line transects |

| + | | | ||

| + | |Tiédoué et al. 2016 | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2015 | + | |2015 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |||

|0.57 | |0.57 | ||

| − | |entire | + | |0.099 (0.060-0.169) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |540 (321-909) |

| − | |Tiédoué et al. 2015 | + | |entire |

| + | |Line transects | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |Tiédoué et al. 2015 | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2014 | + | |2014 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |||

|0.67 | |0.67 | ||

| + | |0.044 (0.022-0.091) | ||

| + | |238 (116-487) | ||

|entire | |entire | ||

| − | |Line transects | + | |Line transects |

| − | |Tiédoué et al. 2014 | + | | |

| + | |Tiédoué et al. 2014 | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2013 | + | |2013 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.055 (0.032-0.093) | + | |0.49 |

| − | | | + | |0.055 (0.032-0.093) |

| − | |entire | + | |294 (173-500) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| − | |Tiédoué et al. 2013 | + | |Line transects |

| + | | | ||

| + | |Tiédoué et al. 2013 | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2012 | + | |2012 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.0493 (0.0252-0.0966) | + | |0.39 |

| − | | | + | |0.0493 (0.0252-0.0966) |

| − | |entire | + | |264(135-518) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| − | |Yapi et al. 2012 | + | |Line transects |

| + | | | ||

| + | |Yapi et al. 2012 | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2011 | + | |2011 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.09 (0.05-0.16) | + | |0.58 |

| − | | | + | |0.09 (0.05-0.16) |

| − | |entire | + | |497 (287-868) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| + | |Line transects | ||

| + | | | ||

|N'Goran et al. 2011 | |N'Goran et al. 2011 | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 133: | Line 142: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2010 | + | |2010 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.08 (0.05-0.14) | + | |0.89 |

| − | | | + | |0.08 (0.05-0.14) |

| − | |entire | + | |441 (264-735) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| + | |Line transects | ||

| + | | | ||

|N'Goran et al. 2010 | |N'Goran et al. 2010 | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 144: | Line 155: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2009 | + | |2009 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.077 (0.040-0.147) | + | |1.22 |

| − | | | + | |0.077 (0.040-0.147) |

| − | |entire | + | |361 (230-568) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| + | |Line transects | ||

| + | | | ||

|N'Goran et al. 2009 | |N'Goran et al. 2009 | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 155: | Line 168: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2008 | + | |2008 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.10 (0.06-0.16) | + | |0.91 |

| − | | | + | |0.10 (0.06-0.16) |

| − | |entire | + | |516 (314-847) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| + | |Line transects | ||

| + | | | ||

|N'Goran et al. 2008 | |N'Goran et al. 2008 | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 166: | Line 181: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2007 | + | |2007 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.09 (0.06-0.14) | + | |0.54 |

| − | | | + | |0.09 (0.06-0.14) |

| − | |entire | + | |479 (299-767) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| + | |Line transects | ||

| + | | | ||

|N'Goran et al. 2007 | |N'Goran et al. 2007 | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 177: | Line 194: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|''Pan troglodytes verus'' | |''Pan troglodytes verus'' | ||

| − | |2006 | + | |2006 |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |0.089 (0.052-0.155) | + | |0.54 |

| − | | | + | |0.089 (0.052-0.155) |

| − | |entire | + | |480 (280-830) |

| − | |Line transects | + | |entire |

| + | |Line transects | ||

| + | | | ||

|N'Goran et al. 2006 | |N'Goran et al. 2006 | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 188: | Line 207: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | = Threats = | + | |

| + | = Threats = | ||

Illegal poaching represents the major threat to the chimpanzee population in the park. Habitat destruction by agriculture, illegal logging and gold mining in some areas of the park also threatens the long-term existence of chimpanzees. Furthermore, long-term research by the Taï Chimpanzee Project and the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin confirmed that Ebola virus (Formenti et al., 1999), Anthrax (Leendertz et al. 2004) and respiratory diseases of human origin (Köndgen et al., 2008) killed a considerable number of chimpanzees. | Illegal poaching represents the major threat to the chimpanzee population in the park. Habitat destruction by agriculture, illegal logging and gold mining in some areas of the park also threatens the long-term existence of chimpanzees. Furthermore, long-term research by the Taï Chimpanzee Project and the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin confirmed that Ebola virus (Formenti et al., 1999), Anthrax (Leendertz et al. 2004) and respiratory diseases of human origin (Köndgen et al., 2008) killed a considerable number of chimpanzees. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | '''Table 3 | + | '''Table 3. Threats to apes reported for Taï National Park''' |

| − | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class=" | + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="Threats-table" |

| − | ! | + | !Category |

| − | !Specific threats | + | !Specific threats |

| − | !Threat level | + | !Threat level |

| − | + | !Description | |

| − | !Description | + | !Year of threat |

| − | !Year of threat | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |1 | + | |1 Residential & commercial development |

| | | | ||

|Absent | |Absent | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |6 | + | |6 Human intrusions & disturbance |

| | | | ||

|Absent | |Absent | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |7 | + | |7 Natural system modifications |

| | | | ||

|Absent | |Absent | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |9 Pollution |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | |Absent |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |10 Geological events |

| | | | ||

|Absent | |Absent | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |12 Other threat |

| | | | ||

|Absent | |Absent | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 11 | + | |5 Biological resource use |

| + | |5.1 Hunting & collecting terrestrial animals | ||

| + | |High (more than 70% of population affected) | ||

| + | |Poaching is widespread throughout the park (Tiédoué et al. 2016, UNESCO 2019b). | ||

| + | |Ongoing (2019) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | ||

| + | |8.1 Invasive non-native/alien species | ||

| + | |High (more than 70% of population affected) | ||

| + | |Chimpanzees died of respiratory diseases of human origin (Köndgen et al. 2008). | ||

| + | |Ongoing (2008) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | ||

| + | |8.2 Problematic native species | ||

| + | |High (more than 70% of population affected) | ||

| + | |Several chimpanzees died due to an Ebola Virus Disease (Taï Forest Ebolavirus) outbreak in the park in 1994 (Formenti et al. 1999). | ||

| + | |1994 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | ||

| + | |8.2 Problematic native species | ||

| + | |High (more than 70% of population affected) | ||

| + | |Anthrax is present at the site and has led to several chimpanzee deaths, first detected in 1996 (Leendertz et al. 2004, Hoffmann et al. 2017). | ||

| + | |1996-Ongoing (2017) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |2 Agriculture & aquaculture | ||

| + | |2.1 Annual & perennial non-timber crops | ||

| + | |Low (up to 30% of population affected) | ||

| + | |Cocoa and rice field in the eastern side of the park (Tiédoué et al. 2016). | ||

| + | |Ongoing (2016) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |3 Energy production & mining | ||

| + | |3.2 Mining & quarrying | ||

| + | |Medium (30-70% of population affected) | ||

| + | |Artisanal gold mining (Tiédoué et al. 2016, UNESCO 2019b). | ||

| + | |Ongoing (2019) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |4 Transportation & service corridors | ||

| + | |4.1 Roads & railroads | ||

| + | |Medium (30-70% of population affected) | ||

| + | |Trails used by poachers (Tiédoué et al. 2016). | ||

| + | |Ongoing (2016) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |11 Climate change & severe weather | ||

| | | | ||

|Unknown | |Unknown | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | = Conservation activities = | + | [https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/threat-classification-scheme IUCN Threats list] |

| + | |||

| + | = Conservation activities = | ||

In the 1970's the first research station was built in Taï National Park and since then several research projects have been conducted on different species. In particular, long-term studies by the Taï Chimpanzee Project (TCP) established in 1979 and the Taï Monkey Project (TMP) established in 1989 ensured and continue to ensure the presence of researchers at the research sites, which have been shown to have a positive influence on local chimpanzee densities (Campbell et al. 2011). Office Ivoirien des Parcs et Reserves (OIPR) does an annual bio-monitoring survey over the entire park and, in addition, the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (WCF) also does an annual bio-monitoring survey over the research area in collaboration with the TCP. OIPR and WCF also conduct regular patrols across the entire park to control for illegal human activities. A range of environmental awareness activities have been implemented, including an eco-museum in Taï, theater plays, movie presentations, newsletters, Club P.A.N., radio shows (WCF 2015, 2018). Two Eco-tourism projects have been developed in the Taï and Djouroutou area. Finally, the Taï Chimpanzee Project is implementing a set of measures to prevent the transmission of human diseases to the chimpanzees (Grützmacher et al. 2018). | In the 1970's the first research station was built in Taï National Park and since then several research projects have been conducted on different species. In particular, long-term studies by the Taï Chimpanzee Project (TCP) established in 1979 and the Taï Monkey Project (TMP) established in 1989 ensured and continue to ensure the presence of researchers at the research sites, which have been shown to have a positive influence on local chimpanzee densities (Campbell et al. 2011). Office Ivoirien des Parcs et Reserves (OIPR) does an annual bio-monitoring survey over the entire park and, in addition, the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (WCF) also does an annual bio-monitoring survey over the research area in collaboration with the TCP. OIPR and WCF also conduct regular patrols across the entire park to control for illegal human activities. A range of environmental awareness activities have been implemented, including an eco-museum in Taï, theater plays, movie presentations, newsletters, Club P.A.N., radio shows (WCF 2015, 2018). Two Eco-tourism projects have been developed in the Taï and Djouroutou area. Finally, the Taï Chimpanzee Project is implementing a set of measures to prevent the transmission of human diseases to the chimpanzees (Grützmacher et al. 2018). | ||

| − | + | '''Table 4. Conservation activities reported for Taï National Park''' | |

| − | '''Table 4 | + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="Conservation_activities-table" |

| − | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class=" | + | !Category |

| − | ! | + | !Specific activity |

| − | !Specific activity | + | !Description |

| − | !Description | + | !Implementing organization(s) |

| − | !Year of activity | + | !Year of activity |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |1 | + | |1 Development impact mitigation |

| − | | | + | |1.15 Certify products from agriculture, mining or logging and market them as ape friendly |

| − | | | + | |support unions of female farmers in the commercialization and promotion of ‘zero deforestation’ agricultural products, including honey from bee-keeping, makore butter, and cacao (WCF 2018) |

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Ongoing (2018) | |Ongoing (2018) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |2 Counter-wildlife crime |

| − | + | |2.3 Conduct regular anti-poaching patrols | |

| − | + | |anti-poaching patrols conducted by OIPR and WCF (WCF 2018) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Ongoing (2018) | |Ongoing (2018) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |2 Counter-wildlife crime | ||

| + | |2.11 Implement monitoring surveillance strategies (e.g., SMART) or use monitoring data to improve effectiveness of patrols | ||

| + | |anti-poaching patrols use SMART (WCF 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Ongoing (2018) | |Ongoing (2018) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |3 Species health |

| − | | | + | |3.1 Wear face-masks to avoid transmission of viral and bacterial diseases to primates |

| + | |mandatory to wear face-masks (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 2004 | |since 2004 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |3 Species health | ||

| + | |3.2 Keep safety distance to habituated apes | ||

| + | |minimum viewing distance of 7 m (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 1999 | |since 1999 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |3 Species health | ||

| + | |3.4 Implement quarantine for people arriving at, and leaving the site | ||

| + | |quarantine in a separate quarantine camp (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 2008 | |since 2008 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |3 Species health | ||

| + | |3.6 Ensure that researchers/tourists are up-to-date with vaccinations and healthy | ||

| + | |visitors have to be vaccinated against measles, all researchers have to be up-to-date with vaccines (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 2008 | |since 2008 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |3 Species health | ||

| + | |3.7 Regularly disinfect clothes, boots etc. | ||

| + | |‘hygiene barrier’ implemented mandating changing clothes and disinfecting boots (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 2002 | |since 2002 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |3 Species health | ||

| + | |3.11 Implement continuous health monitoring/permanent vet on site | ||

| + | |veterinary at research site since 2000 (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 2000 | |since 2000 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |3 Species health | ||

| + | |3.12 Detect and report dead apes and clinically determine their cause of death to avoid disease transmission | ||

| + | |done by the veterinary (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 2000 | |since 2000 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |4 Education & awareness |

| − | | | + | |4.1 Educate local communities about apes and sustainable use |

| + | |environmental awareness raising activities include eco-museum, community meetings, extra-curricular activities in schools Club P.A.N., radio shows, newsletters, theater plays with discussion rounds and movie presentations (WCF 2015, WCF 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Ongoing (2018) | |Ongoing (2018) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |4 Education & awareness | ||

| + | |4.2 Involve local community in ape research and conservation management | ||

| + | |people hired and trained by research and conservation projects (Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019, Taï Monkey Project 2019, WCF 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Ongoing (2019) | |Ongoing (2019) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |4 Education & awareness | ||

| + | |4.4 Regularly play TV and radio announcements to raise ape conservation awareness | ||

| + | |several sets of radio programs played regularly (WCF 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Ongoing (2018) | |Ongoing (2018) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |4 Education & awareness | ||

| + | |4.5 Implement multimedia campaigns using theatre, film, print media, discussions | ||

| + | |theater tour, community discussions, radio, environmental days, eco-museum (WCF 2015, WCF 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Ongoing (2018) | |Ongoing (2018) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |5 Protection & restoration |

| − | | | + | |5.2 Legally protect ape habitat |

|designated as National Park in 1972 (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN 2019) | |designated as National Park in 1972 (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN 2019) | ||

| + | | | ||

|since 1972 | |since 1972 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |8 Permanent presence |

| − | | | + | |8.1 Run research project and ensure permanent human presence at site |

| − | | | + | |3 long-term research projects: Tai Chimpanzee Project (since 1979, Boesch & Boesch-Achermann 2000, Wittig 2018), Tai Monkey Project (since 1989, McGraw et al. 2007) and Tai Hippo Project (since 2013, IBREAM 2018) |

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 1979 | |since 1979 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |8 Permanent presence | ||

| + | |8.2 Run tourist projects and ensure permanent human presence at site | ||

| + | |2 ecotourism sites (Taï and Djouroutou, initiated in 2013, WCF 2015, WCF 2018) | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 2013 | |since 2013 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |8 Permanent presence | ||

| + | |8.3 Permanent presence of staff/manager | ||

| + | |Boesch & Boesch-Achermann 2000, McGraw et al. 2007, Wittig 2018 | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|since 1979 | |since 1979 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Conservation activities list (Junker et al. 2017)]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Challenges = | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Table 5. Challenges reported for Taï National Park''' | ||

| + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="Challenges-table" | ||

| + | !Challenges | ||

| + | !Specific challenges | ||

| + | !Source | ||

| + | !Year(s) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |Not reported | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | = Enablers = | |

| + | |||

| − | '''Table | + | '''Table 6. Enablers reported for Taï National Park''' |

| − | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class=" | + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="enabler-table" |

| − | ! | + | !Enablers |

| − | !Source | + | !Specific enablers |

| + | !Source | ||

| + | !Year(s) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |1 Site management | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |2 Resources and capacity | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |3 Engaged community |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |4 Institutional support | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |5 Ecological context | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |6 Safety and stability | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | = Research activities = | + | |

| + | = Research activities = | ||

Since 1979 chimpanzees have been studied in Taï National Park by the Taï Chimpanzee Project (Tai Chimpanzee Project 2019), while the Taï Monkey Project studies different monkey species since 1989 (Tai Monkey Project 2019). A wide range of topics have been studied including behavior, culture, feeding ecology, sociality, health, biomonitoring methods, and conservation interventions. Since 2013, research is also ongoing on the pygmy hippo (IBREAM 2018). | Since 1979 chimpanzees have been studied in Taï National Park by the Taï Chimpanzee Project (Tai Chimpanzee Project 2019), while the Taï Monkey Project studies different monkey species since 1989 (Tai Monkey Project 2019). A wide range of topics have been studied including behavior, culture, feeding ecology, sociality, health, biomonitoring methods, and conservation interventions. Since 2013, research is also ongoing on the pygmy hippo (IBREAM 2018). | ||

| − | + | = Documented behaviours = | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| − | '''Table | + | '''Table 7. Behaviours documented for Taï National Park''' |

| − | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class=" | + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="behaviours-table" |

| − | ! | + | !Behavior |

| − | !Source | + | !Source |

|- | |- | ||

|Ant dipping | |Ant dipping | ||

| Line 528: | Line 569: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | = Exposure to climate change impacts = |

| + | |||

| + | As part of a study on the exposure of African great ape sites to climate change impacts, Kiribou et al. (2024) extracted climate data and data on projected extreme climate impact events for the site. Climatological characteristics were derived from observation-based climate data provided by the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project ([ISIMIP www.isimip.org]). Parameters were calculated as the average across each 30-year period. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For future projections, two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) were used. RCP 2.6 is a scenario with strong mitigation measures in which global temperatures would likely rise below 2°C. RCP 6.0 is a scenario with medium emissions in which global temperatures would likely rise up to 3°C by 2100. For the number of days with heavy precipitation events, the 98th percentile of all precipitation days (>1mm/d) was calculated for the 1979-2013 reference period as a threshold for a heavy precipitation event. Then, for each year, the number of days above that threshold was derived. The figures on temperature and precipitation anomaly show the deviation from the mean temperature and mean precipitation for the 1979-2013 reference period. The estimated exposure to future extreme climate impact events (crop failure, drought, river flood, wildfire, tropical cyclone, and heatwave) is based on a published dataset by Lange et al. 2020 derived from ISIMIP2b data. The same global climate models and RCPs as described above were used. Within each 30-year period, the number of years with an extreme event and the average proportion of the site affected were calculated (Kiribou et al. 2024). | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Table 8. Estimated past and projected climatological characteristics in Taï National Park''' | ||

| + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="clima-table" | ||

| + | !'''Value''' | ||

| + | !'''1981-2010''' | ||

| + | !'''2021-2050, RCP 2.6''' | ||

| + | !'''2021-2050, RCP 6.0''' | ||

| + | !'''2071-2099, RCP 2.6''' | ||

| + | !'''2071-2099, RCP 6.0''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Mean temperature [°C] | ||

| + | |25.7 | ||

| + | |26.8 | ||

| + | |26.7 | ||

| + | |26.9 | ||

| + | |28 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Annual precipitation [mm] | ||

| + | |1828 | ||

| + | |1822 | ||

| + | |1894 | ||

| + | |1869 | ||

| + | |1947 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Max no. consecutive dry days (per year) | ||

| + | |24 | ||

| + | |23.3 | ||

| + | |22.7 | ||

| + | |24.9 | ||

| + | |24.2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |No. days with heavy precipitation (per year) | ||

| + | |6.4 | ||

| + | |7.8 | ||

| + | |7.5 | ||

| + | |9.5 | ||

| + | |10.3 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Table 9. Projected exposure of apes to extreme climate impact events in Taï National Park''' | ||

| + | {| border="1" cellpadding="5" cellspacing="0" class="clima2-table" | ||

| + | !'''Type''' | ||

| + | !'''No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 2.6)''' | ||

| + | !'''% of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 2.6)''' | ||

| + | !'''No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 6.0)''' | ||

| + | !'''% of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 6.0)''' | ||

| + | !'''No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 2.6)''' | ||

| + | !'''% of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 2.6)''' | ||

| + | !'''No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 6.0)''' | ||

| + | !'''% of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 6.0)''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Crop failure | ||

| + | |3 | ||

| + | |1.11 | ||

| + | |2.5 | ||

| + | |0.83 | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |0.62 | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |1.27 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Drought | ||

| + | |0.5 | ||

| + | |12.5 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0.25 | ||

| + | |12.5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Heatwave | ||

| + | |13.5 | ||

| + | |77.15 | ||

| + | |11.5 | ||

| + | |87.19 | ||

| + | |15.5 | ||

| + | |85.94 | ||

| + | |17.5 | ||

| + | |81.94 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |River flood | ||

| + | |1.25 | ||

| + | |1.46 | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |3.22 | ||

| + | |4.25 | ||

| + | |2.57 | ||

| + | |5.25 | ||

| + | |4.16 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Tropical cyclone | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Wildfire | ||

| + | |30 | ||

| + | |0.51 | ||

| + | |30 | ||

| + | |0.5 | ||

| + | |29 | ||

| + | |0.54 | ||

| + | |29 | ||

| + | |0.54 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div><ul><li style="display: inline-block; vertical-align: top;"> [[File: PrecipAnomaly Tai NP.png | 400px | thumb| right | Precipitation anomaly in Taï National Park]] </li><li style="display: inline-block; vertical-align: top;"> [[File: TempAnomaly Tai NP.png | 400px | thumb| right | Temperature anomaly in Taï National Park]] </li></ul></div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | = External links = | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | = Relevant datasets = | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

= References = | = References = | ||

| − | BirdLife International. 2019 Important Bird Areas factsheet: Parc National de Taï et Réserve de faune du N'Zo. Online: [http://datazone.birdlife.org/site/factsheet/parc-national-de-ta%C3%AF-et-r%C3%A9serve-de-faune-du-nzo-iba-c%C3%B4te-divoire/text www.birdlife.org] | + | |

| − | Boesch C & Boesch-Achermann H. 2000. The chimpanzees of the Taı¨ Forest: behavioural ecology and evolution. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. | + | BirdLife International. 2019 Important Bird Areas factsheet: Parc National de Taï et Réserve de faune du N'Zo. Online: [http://datazone.birdlife.org/site/factsheet/parc-national-de-ta%C3%AF-et-r%C3%A9serve-de-faune-du-nzo-iba-c%C3%B4te-divoire/text www.birdlife.org] |

| − | Campbell, G., Kuehl, H., N´Goran, K.P. and Boesch, C.(2008). Alarming decline of West African chimpanzees in Côte d´Ivoire. Current Biology, 18(19). | + | |

| − | Campbell, G., Kuehl, H., Diarrassouba, A., N’Goran, P. K., and Boesch, C. (2011). Long-term research sites as refugia for threatened and over-harvested species. Biol. Lett. 7, 723–726. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0155 | + | Boesch C & Boesch-Achermann H. 2000. The chimpanzees of the Taı¨ Forest: behavioural ecology and evolution. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. |

| − | Cappelle N et al. 2019. Validating camera trap distance sampling for chimpanzees. American Journal of Primatology 81(3): e22962 | + | |

| − | + | Campbell, G., Kuehl, H., N´Goran, K.P. and Boesch, C.(2008). Alarming decline of West African chimpanzees in Côte d´Ivoire. Current Biology, 18(19). | |

| − | Formenty, P., Boesch, C., Wyers, M., Steiner, C., Donati, F., Dind, F., Walker, F., Le Guenno, B. (1999). Ebola virus outbreak among wild chimpanzees in a rainforest of Côte d'Ivoire. J.Infect.Dis., 179(1): 120-126. | + | |

| − | Grützmacher K et al. 2018. Human quarantine: Toward reducing infectious pressure on chimpanzees at the Taï Chimpanzee Project, Côte d’Ivoire. American Journal of Primatology 80:e22619 | + | Campbell, G., Kuehl, H., Diarrassouba, A., N’Goran, P. K., and Boesch, C. (2011). Long-term research sites as refugia for threatened and over-harvested species. Biol. Lett. 7, 723–726. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0155 |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Cappelle N et al. 2019. Validating camera trap distance sampling for chimpanzees. American Journal of Primatology 81(3): e22962 | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Formenty, P., Boesch, C., Wyers, M., Steiner, C., Donati, F., Dind, F., Walker, F., Le Guenno, B. (1999). Ebola virus outbreak among wild chimpanzees in a rainforest of Côte d'Ivoire. J.Infect.Dis., 179(1): 120-126. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Grützmacher K et al. 2018. Human quarantine: Toward reducing infectious pressure on chimpanzees at the Taï Chimpanzee Project, Côte d’Ivoire. American Journal of Primatology 80:e22619 | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Hoffmann, C., Zimmermann, F., Biek, R., Kuehl, H., Nowak, K., Mundry, R., ... & Leendertz, F. H. (2017). Persistent anthrax as a major driver of wildlife mortality in a tropical rainforest. Nature, 548(7665), 82-86. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Hoppe-Dominik, B. (1991) Distribution and status of chimpanzees ''(Pan troglodytes verus)'' on the Ivory Coast. Primate Report, 31, 45-75. | |

| − | N’Goran, K.P., Herbinger, I., Boesch, C., Tondossama, A. (2007). | + | |

| − | N’Goran, K.P., Yapi, F. Herbinger, I., Boesch, C., Tondossama, A. ( | + | IBREAM. 2018. Pygmy Hippo PhD 2017 Summary. Institute for Breeding Rare and Endangered African Mammals. [https://ibream.org/updates/pygmy-hippo-phd-2017-summary/ Taï Hippo Project] |

| − | N’Goran, K.P., Yapi, F. Herbinger, I., Boesch, C | + | |

| − | N’Goran | + | Klee, S.R., Oetzel, M., Appel, B., Boesch, C., Ellerbrock, H., Jacob, D., Holland, G., Leendertz, F.H., Pauli, G., Grunow, R., Nattermann, H. (2006). Characterization of Bacillus anthracis-like Bacteria Isolated from Wild Great Apes from Côte d'Ivoire and Cameroon. Journal of Bacteriology, 188 (15): 5333-5344. |

| − | N’Goran K. P., Yapi A. F., Herbinger I., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. | + | |

| − | + | Köndgen, S., Kuehl, H., N´Goran, K.P., Walsh, P., Schenk, S., Ernst, N., Biek, R., Formenty, P., Mätz-Rensing, K., Schweiger, B., Junglen, S., Ellerbrok, H., Nitsche, A., Briese, T., Lipkin, W.I., Pauli, G., Boesch, C., Leendertz, F.H. (2008). Pandemic Human Viruses Causes Decline of Endangered Great Apes. Current Biology 18, 260-264. | |

| − | Tai | + | |

| − | + | Kiribou, R., Tehoda, P., Chukwu, O., Bempah, G., Kühl, H. S., Ferreira, J., ... & Heinicke, S. (2024). Exposure of African ape sites to climate change impacts. PLOS Climate, 3(2), e0000345. | |

| − | Tiédoué R | + | |

| − | Tiédoué R., | + | Kouakou CY, Boesch C, and Kuehl H. 2009. Estimating chimpanzee population size with nest counts: validating methods in Taï National Park. Am. J. Primatol. 71, 447–457. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20673 |

| − | Tiédoué | + | |

| − | + | Kühl HS et al. 2019. Human impact erodes chimpanzee behavioral diversity. Science. 363, 1453–1455. | |

| − | Radl, G. 2004. Le système de surveillance et le développement des densités des animaux braconnés du Parc National de Taï. Deutschen Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Eschborn, PN: 02.2279.4-001.00. | + | |

| − | UICN/BRAO (2008). Evaluation de l’éfficacité de la gestion des aires protégées: parcs et réserves de Côte d´Ivoire. | + | Leendertz, F.H., Ellerbrok, H., Boesch, C., Couacy-Hymann, E., Mätz-Rensing, K., Hakenbeck, R., Bergmann, C., Abaza, P., Junglen, S., Moebius, Y., Vigilant, L., Formenty, P., Pauli, G. (2004). Anthrax kills wild chimpanzees in a tropical rain forest, Nature, 430. |

| − | UNEP-WCMC, IUCN. 2019. Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC and IUCN Online: [https://www.protectedplanet.net/tai-national-park-national-park www.protectedplanet.net] | + | |

| − | UNESCO. 2019a. Taï National Park [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/195/ unesco.org] | + | Luncz L. and Boesch C. 2015 The Extent of Cultural Variation Between Adjacent Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) Communities; A Microecological Approach American Journal of Physical Anthropology 156: 67-75 |

| − | UNESCO. 2019b. State of Conservation - Taï National Park. Online: [http://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/3920 unesco.org] | + | |

| − | WCF. 2015 Annual report 2015 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: [https://www.wildchimps.org/reports/reports.html Wild Chimpanzee Foundation] | + | Marchesi, P., Marchesi,N., Fruth, B. and Boesch, C. (1995). Census and Distribution in Côte D´Ivoire. Primates, 36(4): 591-607. |

| − | WCF. 2017. Annual report 2017 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: [https://www.wildchimps.org/reports/reports.html Wild Chimpanzee Foundation] | + | |

| − | WCF. 2018. Annual report 2018 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: [https://www.wildchimps.org/reports/reports.html Wild Chimpanzee Foundation] | + | McGraw WS et al. 2007. Monkeys of the Taï Forest: An African Primate Community. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. UK |

| − | WCF, OIPR-PNT, WWF, CSRS, KFW, EU, UNEP, GRASP and GTZ. 2008. Etat du Parc National de Tai. Rapport de Resultats de Biomonitoring Phase III (Août 2007-Mars 2008) | + | |

| − | Whiten et al. 1999. Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature 399: 682-685 | + | N’Goran, K.P., Herbinger, I., Boesch, C., Tondossama, A. (2007). Quelques résultats de la première phase du biomonitoring au Parc National de Taï (août 2005 – mars 2006). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR. |

| − | Wittig R. 2018. 40 years of research at the Taï Chimpanzee Project. Pan Africa News 25(2): 16-18 | + | |

| − | Yao, C. Y. Adou and Roussel, Bernard (2007). Forest Management, Farmers' Practices and Biodiversity Conservation in the Monogaga Protected Coastal Forest in Southwest Côte D'Ivoire. Africa, 77(1):63-85. | + | N’Goran, K.P., Yapi, F. Herbinger, I., Boesch, C., Tondossama, A. (2007). /Etat du Parc National de Taï /: Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring, phase II (septembre 2006 – avril 2007). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR. |

| − | Yapi A. F., Vergnes V., Normand E., N’Goran K. P., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2012 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase 7 (janvier 2012- juillet 2012). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan. | + | |

| + | N’Goran, K.P., Yapi, F. Herbinger, I., Boesch, C., Tondossama, A. (2008). /Etat du Parc National de Taï./ Rapport de resultats de biomonitoring. Phase III, Août 2007 - Mars 2008. Unpubl. Report WCF/OIPR. | ||

| + | |||

| + | N’Goran, K. P., Yapi, A. F., Herbinger, I., Tondossama, A. et Boesch, C. (2009). Etat du Parc National de Taï : Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase IV (août 2008 – février 2009). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | N’Goran K. P., Yapi A. F., Herbinger I., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2009 - Etat du Parc National de Taï : Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase V (septembre 2009 – mars 2010). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | N’Goran K. P., Yapi A. F., Normand E., Herbinger I., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2011 - Etat du Parc National de Taï : Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase VI (octobre 2010 – mars 2011). Unpubl.Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tai Chimpanzee Project. 2019. Taï Chimpanzee Project. Online : [https://www.eva.mpg.de/primat/research-groups/chimpanzees/field-sites/tai-chimpanzee-project.html Taï Chimpanzee Project] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tai Monkey Project. 2019. Tai Monkey Project. Online: [https://www.taimonkeys.org Tai Monkey Project] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tiédoué R., Vergnes V., Kouakou Y. C., Normand E., Ouattara M., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2013 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de suivi-écologique - phase 8 (janvier 2013 - juin 2013). Unpubl. Rapport OIPR/WCF, Abidjan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tiédoué R., Kouakou Y. C., Normand E., Vergnes V., Ouattara M., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2014 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de suivi-écologique - phase 9 (octobre 2013 - avril 2014). Unpubl. Rapport OIPR/WCF, Abidjan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tiédoué R., Normand E., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2015 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de suivi-écologique - phase 10 (novembre 2014 - mai 2015). Unpubl. Rapport OIPR/WCF, Abidjan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tiédoué R., Diarrassouba A. et Tondossama A. 2016 – Etat de conservation du Parc national de Taï: Résultats du suivi écologique, Phase 11. Office Ivoirien des Parcs et Réserves/Direction de Zone Sud-ouest. Soubré, Unpubl. Côte d’Ivoire. 31p. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Radl, G. 2004. Le système de surveillance et le développement des densités des animaux braconnés du Parc National de Taï. Deutschen Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Eschborn, PN: 02.2279.4-001.00. | ||

| + | |||

| + | UICN/BRAO (2008). Evaluation de l’éfficacité de la gestion des aires protégées: parcs et réserves de Côte d´Ivoire. | ||

| + | |||

| + | UNEP-WCMC, IUCN. 2019. Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC and IUCN Online: [https://www.protectedplanet.net/tai-national-park-national-park www.protectedplanet.net] | ||

| + | |||

| + | UNESCO. 2019a. Taï National Park [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/195/ unesco.org] | ||

| + | |||

| + | UNESCO. 2019b. State of Conservation - Taï National Park. Online: [http://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/3920 unesco.org] | ||

| + | |||

| + | WCF. 2015 Annual report 2015 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: [https://www.wildchimps.org/reports/reports.html Wild Chimpanzee Foundation] | ||

| + | |||

| + | WCF. 2017. Annual report 2017 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: [https://www.wildchimps.org/reports/reports.html Wild Chimpanzee Foundation] | ||

| + | |||

| + | WCF. 2018. Annual report 2018 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: [https://www.wildchimps.org/reports/reports.html Wild Chimpanzee Foundation] | ||

| + | |||

| + | WCF, OIPR-PNT, WWF, CSRS, KFW, EU, UNEP, GRASP and GTZ. 2008. Etat du Parc National de Tai. Rapport de Resultats de Biomonitoring Phase III (Août 2007-Mars 2008) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Whiten et al. 1999. Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature 399: 682-685 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wittig R. 2018. 40 years of research at the Taï Chimpanzee Project. Pan Africa News 25(2): 16-18 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yao, C. Y. Adou and Roussel, Bernard (2007). Forest Management, Farmers' Practices and Biodiversity Conservation in the Monogaga Protected Coastal Forest in Southwest Côte D'Ivoire. Africa, 77(1):63-85. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yapi A. F., Vergnes V., Normand E., N’Goran K. P., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2012 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase 7 (janvier 2012- juillet 2012). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan. | ||

| + | |||

| − | + | '''Page created by: '''Julia Riedel & A.P.E.S. Wiki team''' Date:''' NA | |

| − | '''Page | ||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 09:57, 18 March 2025

West Africa > Côte d'Ivoire > Taï National Park

Français | Português | Español | Bahasa Indonesia | Melayu

Summary

- Western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) are present in Taï National Park.

- It has been estimated that 406 (CI: 265-623) individuals occur at the site.

- The chimpanzee population trend is stable.

- This site has a total size of 5,0812 km².

- Key threats to chimpanzees are poaching and diseases.

- A range of conservation activities are implemented, including permanent presence of researchers and tourists, anti-poaching patrols, environmental education and measures to prevent disease transmission to chimpanzees.

- Taï National Park is the largest remaining forest block in the Upper Guinea Region and is home to one of the longest-running chimpanzee research sites.

Site characteristics

Taï National Park (IUCN category: II) was created in 1972 and proclaimed a UNESCO world heritage site in 1982 (Criteria iii, iv, UNESCO 2019a). The park is located in south-western Côte d'Ivoire (5°15'-6°07'N, 7°25'-7°54'W), approximately 200 km south of Man and 100 km from the coast. With a size of 5,0812 km², it is the largest protected forest block in Côte d’Ivoire and one of the last tropical lowland forests in the Upper Guinea Region. The topography is mostly flat, but some Inselbergs occur. The majority of the forest in the park has never been logged and this mature, old-growth forest supports a rich diversity of species. It has been estimated that around 1,300 plant species occur in the park, 80-150 are endemic to the Upper Guinea region (BirdLife International 2019). Because of its diversity of bird species, notably white-breasted guinea fowl (Agelastes meleagrides) and large hornbill species, it is considered an Important Bird Area (BirdLife International 2019). Primate species recorded in the park include olive colobus (Procolobus verus), western red colobus (Piliocolobus badius), king colobus (Colobus polykomos), and Diana monkey (Cercopithecus diana). Other mammal species include the Pel's flying squirrel (Anomalurus peli), forest elephant (Loxodonta africana ), pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis), Water chevrotain (Hyemoschus aquaticus), African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), and a range of duikers, including Maxwell's duiker (Philantomba maxwellii), black duiker (Cephalophus niger), zebra duiker (Cephalophus zebra), and Jentink's duiker (Cephalophus jentinki). Reptile species include (Crocodylus cataphractus) and African dwarf crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis), Home's hinge-back tortoise (Kinixys homeana).

Table 1. Basic site information for Taï National Park

| Species | 'Pan troglodytes verus |

| Area | 5,0812 km² |

| Coordinates | Lat: 5.77 , Lon: -7.12 |

| Type of site | Protected area (National Park) |

| Habitat types | Subtropical/tropical moist lowland forest, Agricultural land |

| Type of governance |

IUCN habitat categories Site designations

Ape status

Since 2005 annual surveys on western chimpanzees have been implemented by OIPR and the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (WCF). Estimated chimpanzee abundance ranges between 300-800 individuals and the population seems to be stable (Campbell et al. 2008). Since 2016, the WCF has used camera traps to systematically monitor biodiversity in 200 km² in the Taï National Park (Cappelle et al. 2019).

Table 2. Ape population estimates reported for Taï National Park

| Species | Year | Occurrence | Encounter or vistation rate (nests/km; ind/day) | Density estimate [ind./ km²] (95% CI) | Abundance estimate (95% CI) | Survey area | Sampling method | Analytical framework | Source | Comments | A.P.E.S. database ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2016 | 0.265 | 0.07 (0.05-0.11) | 406 (265-623) | entire | Line transects | Tiédoué et al. 2016 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2015 | 0.57 | 0.099 (0.060-0.169) | 540 (321-909) | entire | Line transects | Tiédoué et al. 2015 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2014 | 0.67 | 0.044 (0.022-0.091) | 238 (116-487) | entire | Line transects | Tiédoué et al. 2014 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2013 | 0.49 | 0.055 (0.032-0.093) | 294 (173-500) | entire | Line transects | Tiédoué et al. 2013 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2012 | 0.39 | 0.0493 (0.0252-0.0966) | 264(135-518) | entire | Line transects | Yapi et al. 2012 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2011 | 0.58 | 0.09 (0.05-0.16) | 497 (287-868) | entire | Line transects | N'Goran et al. 2011 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2010 | 0.89 | 0.08 (0.05-0.14) | 441 (264-735) | entire | Line transects | N'Goran et al. 2010 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2009 | 1.22 | 0.077 (0.040-0.147) | 361 (230-568) | entire | Line transects | N'Goran et al. 2009 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2008 | 0.91 | 0.10 (0.06-0.16) | 516 (314-847) | entire | Line transects | N'Goran et al. 2008 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2007 | 0.54 | 0.09 (0.06-0.14) | 479 (299-767) | entire | Line transects | N'Goran et al. 2007 | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2006 | 0.54 | 0.089 (0.052-0.155) | 480 (280-830) | entire | Line transects | N'Goran et al. 2006 |

Threats

Illegal poaching represents the major threat to the chimpanzee population in the park. Habitat destruction by agriculture, illegal logging and gold mining in some areas of the park also threatens the long-term existence of chimpanzees. Furthermore, long-term research by the Taï Chimpanzee Project and the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin confirmed that Ebola virus (Formenti et al., 1999), Anthrax (Leendertz et al. 2004) and respiratory diseases of human origin (Köndgen et al., 2008) killed a considerable number of chimpanzees.

Table 3. Threats to apes reported for Taï National Park

| Category | Specific threats | Threat level | Description | Year of threat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Residential & commercial development | Absent | |||

| 6 Human intrusions & disturbance | Absent | |||

| 7 Natural system modifications | Absent | |||

| 9 Pollution | Absent | |||

| 10 Geological events | Absent | |||

| 12 Other threat | Absent | |||

| 5 Biological resource use | 5.1 Hunting & collecting terrestrial animals | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Poaching is widespread throughout the park (Tiédoué et al. 2016, UNESCO 2019b). | Ongoing (2019) |

| 8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | 8.1 Invasive non-native/alien species | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Chimpanzees died of respiratory diseases of human origin (Köndgen et al. 2008). | Ongoing (2008) |

| 8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | 8.2 Problematic native species | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Several chimpanzees died due to an Ebola Virus Disease (Taï Forest Ebolavirus) outbreak in the park in 1994 (Formenti et al. 1999). | 1994 |

| 8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | 8.2 Problematic native species | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Anthrax is present at the site and has led to several chimpanzee deaths, first detected in 1996 (Leendertz et al. 2004, Hoffmann et al. 2017). | 1996-Ongoing (2017) |

| 2 Agriculture & aquaculture | 2.1 Annual & perennial non-timber crops | Low (up to 30% of population affected) | Cocoa and rice field in the eastern side of the park (Tiédoué et al. 2016). | Ongoing (2016) |

| 3 Energy production & mining | 3.2 Mining & quarrying | Medium (30-70% of population affected) | Artisanal gold mining (Tiédoué et al. 2016, UNESCO 2019b). | Ongoing (2019) |

| 4 Transportation & service corridors | 4.1 Roads & railroads | Medium (30-70% of population affected) | Trails used by poachers (Tiédoué et al. 2016). | Ongoing (2016) |

| 11 Climate change & severe weather | Unknown |

Conservation activities

In the 1970's the first research station was built in Taï National Park and since then several research projects have been conducted on different species. In particular, long-term studies by the Taï Chimpanzee Project (TCP) established in 1979 and the Taï Monkey Project (TMP) established in 1989 ensured and continue to ensure the presence of researchers at the research sites, which have been shown to have a positive influence on local chimpanzee densities (Campbell et al. 2011). Office Ivoirien des Parcs et Reserves (OIPR) does an annual bio-monitoring survey over the entire park and, in addition, the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (WCF) also does an annual bio-monitoring survey over the research area in collaboration with the TCP. OIPR and WCF also conduct regular patrols across the entire park to control for illegal human activities. A range of environmental awareness activities have been implemented, including an eco-museum in Taï, theater plays, movie presentations, newsletters, Club P.A.N., radio shows (WCF 2015, 2018). Two Eco-tourism projects have been developed in the Taï and Djouroutou area. Finally, the Taï Chimpanzee Project is implementing a set of measures to prevent the transmission of human diseases to the chimpanzees (Grützmacher et al. 2018).

Table 4. Conservation activities reported for Taï National Park

| Category | Specific activity | Description | Implementing organization(s) | Year of activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Development impact mitigation | 1.15 Certify products from agriculture, mining or logging and market them as ape friendly | support unions of female farmers in the commercialization and promotion of ‘zero deforestation’ agricultural products, including honey from bee-keeping, makore butter, and cacao (WCF 2018) | Ongoing (2018) | |

| 2 Counter-wildlife crime | 2.3 Conduct regular anti-poaching patrols | anti-poaching patrols conducted by OIPR and WCF (WCF 2018) | Ongoing (2018) | |

| 2 Counter-wildlife crime | 2.11 Implement monitoring surveillance strategies (e.g., SMART) or use monitoring data to improve effectiveness of patrols | anti-poaching patrols use SMART (WCF 2018) | Ongoing (2018) | |

| 3 Species health | 3.1 Wear face-masks to avoid transmission of viral and bacterial diseases to primates | mandatory to wear face-masks (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | since 2004 | |

| 3 Species health | 3.2 Keep safety distance to habituated apes | minimum viewing distance of 7 m (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | since 1999 | |

| 3 Species health | 3.4 Implement quarantine for people arriving at, and leaving the site | quarantine in a separate quarantine camp (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | since 2008 | |

| 3 Species health | 3.6 Ensure that researchers/tourists are up-to-date with vaccinations and healthy | visitors have to be vaccinated against measles, all researchers have to be up-to-date with vaccines (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | since 2008 | |

| 3 Species health | 3.7 Regularly disinfect clothes, boots etc. | ‘hygiene barrier’ implemented mandating changing clothes and disinfecting boots (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | since 2002 | |

| 3 Species health | 3.11 Implement continuous health monitoring/permanent vet on site | veterinary at research site since 2000 (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | since 2000 | |

| 3 Species health | 3.12 Detect and report dead apes and clinically determine their cause of death to avoid disease transmission | done by the veterinary (Grützmacher et al. 2018) | since 2000 | |

| 4 Education & awareness | 4.1 Educate local communities about apes and sustainable use | environmental awareness raising activities include eco-museum, community meetings, extra-curricular activities in schools Club P.A.N., radio shows, newsletters, theater plays with discussion rounds and movie presentations (WCF 2015, WCF 2018) | Ongoing (2018) | |

| 4 Education & awareness | 4.2 Involve local community in ape research and conservation management | people hired and trained by research and conservation projects (Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019, Taï Monkey Project 2019, WCF 2018) | Ongoing (2019) | |

| 4 Education & awareness | 4.4 Regularly play TV and radio announcements to raise ape conservation awareness | several sets of radio programs played regularly (WCF 2018) | Ongoing (2018) | |

| 4 Education & awareness | 4.5 Implement multimedia campaigns using theatre, film, print media, discussions | theater tour, community discussions, radio, environmental days, eco-museum (WCF 2015, WCF 2018) | Ongoing (2018) | |

| 5 Protection & restoration | 5.2 Legally protect ape habitat | designated as National Park in 1972 (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN 2019) | since 1972 | |

| 8 Permanent presence | 8.1 Run research project and ensure permanent human presence at site | 3 long-term research projects: Tai Chimpanzee Project (since 1979, Boesch & Boesch-Achermann 2000, Wittig 2018), Tai Monkey Project (since 1989, McGraw et al. 2007) and Tai Hippo Project (since 2013, IBREAM 2018) | since 1979 | |

| 8 Permanent presence | 8.2 Run tourist projects and ensure permanent human presence at site | 2 ecotourism sites (Taï and Djouroutou, initiated in 2013, WCF 2015, WCF 2018) | since 2013 | |

| 8 Permanent presence | 8.3 Permanent presence of staff/manager | Boesch & Boesch-Achermann 2000, McGraw et al. 2007, Wittig 2018 | since 1979 |

Conservation activities list (Junker et al. 2017)

Challenges

Table 5. Challenges reported for Taï National Park

| Challenges | Specific challenges | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not reported |

Enablers

Table 6. Enablers reported for Taï National Park

| Enablers | Specific enablers | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Site management | |||

| 2 Resources and capacity | |||

| 3 Engaged community | |||

| 4 Institutional support | |||

| 5 Ecological context | |||

| 6 Safety and stability |

Research activities

Since 1979 chimpanzees have been studied in Taï National Park by the Taï Chimpanzee Project (Tai Chimpanzee Project 2019), while the Taï Monkey Project studies different monkey species since 1989 (Tai Monkey Project 2019). A wide range of topics have been studied including behavior, culture, feeding ecology, sociality, health, biomonitoring methods, and conservation interventions. Since 2013, research is also ongoing on the pygmy hippo (IBREAM 2018).

Documented behaviours

Table 7. Behaviours documented for Taï National Park

| Behavior | Source |

|---|---|

| Ant dipping | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Ant eating | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Ant eating without tools | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Branch clasping | Whiten et al. 1999 |

| Branch dragging | Whiten et al. 1999 |

| Branch slapping | Whiten et al. 1999 |

| Buttress beating | Whiten et al. 1999 |

| Fluid dipping | Whiten et al. 1999 |

| Honey eating | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Honey extraction with tools | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Honey extraction without tools | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Knuckle-knock | Whiten et al. 1999 |

| Leaf clipping | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Leaf cushion | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Leaf sponging for drinking water | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Marrow pick | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Nut cracking | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Stone throwing | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Termite eating | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Termite eating without tools | Luncz and Boesch 2015, Kühl et al. 2019, Taï Chimpanzee Project 2019 |

| Wood pounding | Whiten et al. 1999 |

Exposure to climate change impacts

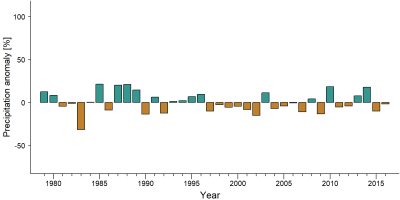

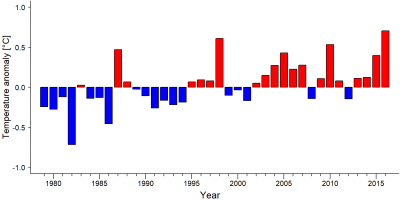

As part of a study on the exposure of African great ape sites to climate change impacts, Kiribou et al. (2024) extracted climate data and data on projected extreme climate impact events for the site. Climatological characteristics were derived from observation-based climate data provided by the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project ([ISIMIP www.isimip.org]). Parameters were calculated as the average across each 30-year period.

For future projections, two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) were used. RCP 2.6 is a scenario with strong mitigation measures in which global temperatures would likely rise below 2°C. RCP 6.0 is a scenario with medium emissions in which global temperatures would likely rise up to 3°C by 2100. For the number of days with heavy precipitation events, the 98th percentile of all precipitation days (>1mm/d) was calculated for the 1979-2013 reference period as a threshold for a heavy precipitation event. Then, for each year, the number of days above that threshold was derived. The figures on temperature and precipitation anomaly show the deviation from the mean temperature and mean precipitation for the 1979-2013 reference period. The estimated exposure to future extreme climate impact events (crop failure, drought, river flood, wildfire, tropical cyclone, and heatwave) is based on a published dataset by Lange et al. 2020 derived from ISIMIP2b data. The same global climate models and RCPs as described above were used. Within each 30-year period, the number of years with an extreme event and the average proportion of the site affected were calculated (Kiribou et al. 2024).

Table 8. Estimated past and projected climatological characteristics in Taï National Park

| Value | 1981-2010 | 2021-2050, RCP 2.6 | 2021-2050, RCP 6.0 | 2071-2099, RCP 2.6 | 2071-2099, RCP 6.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean temperature [°C] | 25.7 | 26.8 | 26.7 | 26.9 | 28 |

| Annual precipitation [mm] | 1828 | 1822 | 1894 | 1869 | 1947 |

| Max no. consecutive dry days (per year) | 24 | 23.3 | 22.7 | 24.9 | 24.2 |

| No. days with heavy precipitation (per year) | 6.4 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 10.3 |

Table 9. Projected exposure of apes to extreme climate impact events in Taï National Park

| Type | No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop failure | 3 | 1.11 | 2.5 | 0.83 | 4 | 0.62 | 4 | 1.27 |

| Drought | 0.5 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 12.5 |

| Heatwave | 13.5 | 77.15 | 11.5 | 87.19 | 15.5 | 85.94 | 17.5 | 81.94 |

| River flood | 1.25 | 1.46 | 4 | 3.22 | 4.25 | 2.57 | 5.25 | 4.16 |

| Tropical cyclone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wildfire | 30 | 0.51 | 30 | 0.5 | 29 | 0.54 | 29 | 0.54 |

External links

Relevant datasets

References

BirdLife International. 2019 Important Bird Areas factsheet: Parc National de Taï et Réserve de faune du N'Zo. Online: www.birdlife.org

Boesch C & Boesch-Achermann H. 2000. The chimpanzees of the Taı¨ Forest: behavioural ecology and evolution. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, G., Kuehl, H., N´Goran, K.P. and Boesch, C.(2008). Alarming decline of West African chimpanzees in Côte d´Ivoire. Current Biology, 18(19).

Campbell, G., Kuehl, H., Diarrassouba, A., N’Goran, P. K., and Boesch, C. (2011). Long-term research sites as refugia for threatened and over-harvested species. Biol. Lett. 7, 723–726. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0155

Cappelle N et al. 2019. Validating camera trap distance sampling for chimpanzees. American Journal of Primatology 81(3): e22962

Formenty, P., Boesch, C., Wyers, M., Steiner, C., Donati, F., Dind, F., Walker, F., Le Guenno, B. (1999). Ebola virus outbreak among wild chimpanzees in a rainforest of Côte d'Ivoire. J.Infect.Dis., 179(1): 120-126.

Grützmacher K et al. 2018. Human quarantine: Toward reducing infectious pressure on chimpanzees at the Taï Chimpanzee Project, Côte d’Ivoire. American Journal of Primatology 80:e22619

Hoffmann, C., Zimmermann, F., Biek, R., Kuehl, H., Nowak, K., Mundry, R., ... & Leendertz, F. H. (2017). Persistent anthrax as a major driver of wildlife mortality in a tropical rainforest. Nature, 548(7665), 82-86.

Hoppe-Dominik, B. (1991) Distribution and status of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) on the Ivory Coast. Primate Report, 31, 45-75.

IBREAM. 2018. Pygmy Hippo PhD 2017 Summary. Institute for Breeding Rare and Endangered African Mammals. Taï Hippo Project

Klee, S.R., Oetzel, M., Appel, B., Boesch, C., Ellerbrock, H., Jacob, D., Holland, G., Leendertz, F.H., Pauli, G., Grunow, R., Nattermann, H. (2006). Characterization of Bacillus anthracis-like Bacteria Isolated from Wild Great Apes from Côte d'Ivoire and Cameroon. Journal of Bacteriology, 188 (15): 5333-5344.

Köndgen, S., Kuehl, H., N´Goran, K.P., Walsh, P., Schenk, S., Ernst, N., Biek, R., Formenty, P., Mätz-Rensing, K., Schweiger, B., Junglen, S., Ellerbrok, H., Nitsche, A., Briese, T., Lipkin, W.I., Pauli, G., Boesch, C., Leendertz, F.H. (2008). Pandemic Human Viruses Causes Decline of Endangered Great Apes. Current Biology 18, 260-264.

Kiribou, R., Tehoda, P., Chukwu, O., Bempah, G., Kühl, H. S., Ferreira, J., ... & Heinicke, S. (2024). Exposure of African ape sites to climate change impacts. PLOS Climate, 3(2), e0000345.

Kouakou CY, Boesch C, and Kuehl H. 2009. Estimating chimpanzee population size with nest counts: validating methods in Taï National Park. Am. J. Primatol. 71, 447–457. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20673

Kühl HS et al. 2019. Human impact erodes chimpanzee behavioral diversity. Science. 363, 1453–1455.

Leendertz, F.H., Ellerbrok, H., Boesch, C., Couacy-Hymann, E., Mätz-Rensing, K., Hakenbeck, R., Bergmann, C., Abaza, P., Junglen, S., Moebius, Y., Vigilant, L., Formenty, P., Pauli, G. (2004). Anthrax kills wild chimpanzees in a tropical rain forest, Nature, 430.

Luncz L. and Boesch C. 2015 The Extent of Cultural Variation Between Adjacent Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) Communities; A Microecological Approach American Journal of Physical Anthropology 156: 67-75

Marchesi, P., Marchesi,N., Fruth, B. and Boesch, C. (1995). Census and Distribution in Côte D´Ivoire. Primates, 36(4): 591-607.

McGraw WS et al. 2007. Monkeys of the Taï Forest: An African Primate Community. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. UK

N’Goran, K.P., Herbinger, I., Boesch, C., Tondossama, A. (2007). Quelques résultats de la première phase du biomonitoring au Parc National de Taï (août 2005 – mars 2006). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR.

N’Goran, K.P., Yapi, F. Herbinger, I., Boesch, C., Tondossama, A. (2007). /Etat du Parc National de Taï /: Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring, phase II (septembre 2006 – avril 2007). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR.

N’Goran, K.P., Yapi, F. Herbinger, I., Boesch, C., Tondossama, A. (2008). /Etat du Parc National de Taï./ Rapport de resultats de biomonitoring. Phase III, Août 2007 - Mars 2008. Unpubl. Report WCF/OIPR.

N’Goran, K. P., Yapi, A. F., Herbinger, I., Tondossama, A. et Boesch, C. (2009). Etat du Parc National de Taï : Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase IV (août 2008 – février 2009). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan.

N’Goran K. P., Yapi A. F., Herbinger I., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2009 - Etat du Parc National de Taï : Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase V (septembre 2009 – mars 2010). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan.

N’Goran K. P., Yapi A. F., Normand E., Herbinger I., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2011 - Etat du Parc National de Taï : Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase VI (octobre 2010 – mars 2011). Unpubl.Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan.

Tai Chimpanzee Project. 2019. Taï Chimpanzee Project. Online : Taï Chimpanzee Project

Tai Monkey Project. 2019. Tai Monkey Project. Online: Tai Monkey Project

Tiédoué R., Vergnes V., Kouakou Y. C., Normand E., Ouattara M., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2013 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de suivi-écologique - phase 8 (janvier 2013 - juin 2013). Unpubl. Rapport OIPR/WCF, Abidjan.

Tiédoué R., Kouakou Y. C., Normand E., Vergnes V., Ouattara M., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2014 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de suivi-écologique - phase 9 (octobre 2013 - avril 2014). Unpubl. Rapport OIPR/WCF, Abidjan.

Tiédoué R., Normand E., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2015 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de suivi-écologique - phase 10 (novembre 2014 - mai 2015). Unpubl. Rapport OIPR/WCF, Abidjan.

Tiédoué R., Diarrassouba A. et Tondossama A. 2016 – Etat de conservation du Parc national de Taï: Résultats du suivi écologique, Phase 11. Office Ivoirien des Parcs et Réserves/Direction de Zone Sud-ouest. Soubré, Unpubl. Côte d’Ivoire. 31p.

Radl, G. 2004. Le système de surveillance et le développement des densités des animaux braconnés du Parc National de Taï. Deutschen Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Eschborn, PN: 02.2279.4-001.00.

UICN/BRAO (2008). Evaluation de l’éfficacité de la gestion des aires protégées: parcs et réserves de Côte d´Ivoire.

UNEP-WCMC, IUCN. 2019. Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC and IUCN Online: www.protectedplanet.net

UNESCO. 2019a. Taï National Park unesco.org

UNESCO. 2019b. State of Conservation - Taï National Park. Online: unesco.org

WCF. 2015 Annual report 2015 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: Wild Chimpanzee Foundation

WCF. 2017. Annual report 2017 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: Wild Chimpanzee Foundation

WCF. 2018. Annual report 2018 – activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Online: Wild Chimpanzee Foundation

WCF, OIPR-PNT, WWF, CSRS, KFW, EU, UNEP, GRASP and GTZ. 2008. Etat du Parc National de Tai. Rapport de Resultats de Biomonitoring Phase III (Août 2007-Mars 2008)

Whiten et al. 1999. Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature 399: 682-685

Wittig R. 2018. 40 years of research at the Taï Chimpanzee Project. Pan Africa News 25(2): 16-18

Yao, C. Y. Adou and Roussel, Bernard (2007). Forest Management, Farmers' Practices and Biodiversity Conservation in the Monogaga Protected Coastal Forest in Southwest Côte D'Ivoire. Africa, 77(1):63-85.

Yapi A. F., Vergnes V., Normand E., N’Goran K. P., Diarrassouba A., Tondossama A. et Boesch C. 2012 - Etat de conservation du Parc National de Taï: Rapport de résultats de biomonitoring phase 7 (janvier 2012- juillet 2012). Unpubl. Rapport WCF/OIPR, Abidjan.

Page created by: Julia Riedel & A.P.E.S. Wiki team Date: NA