Difference between revisions of "Bulindi Area"

(Created page with "East Africa > Uganda > Bulindi Area '''[https://wiki-iucnapesportal-org.translate.goog/index.php/The_A.P.E.S._Wiki?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=fr&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto...") |

|||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

<div style="float: right"> | <div style="float: right"> | ||

{{#display_map: height=200px | width=300px | scrollzoom=off | zoom=5 | layers= OpenStreetMap, OpenTopoMap | {{#display_map: height=200px | width=300px | scrollzoom=off | zoom=5 | layers= OpenStreetMap, OpenTopoMap | ||

| − | | ~[[]]~ | + | |1.483333 , 31.466667~[[Eastern chimpanzees]]~ |

}} | }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 06:25, 29 June 2024

East Africa > Uganda > Bulindi Area

Français | Português | Bahasa Indonesia | Melayu

Summary

- Eastern chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) are present in Bulindi.

- It is estimated that 22 individuals inhabit the site.

- The chimpanzee population trend is decreasing.

- The site has a total size of 25 km².

- Key threats to chimpanzees are habitat loss, human-chimpanzee conflict, lethal crop protection measures, roads, and diseases.

- Conservation activities implemented by the Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project focus on supporting local residents through livelihood alternatives to deforestation, extensive tree planting, investing in children’s education, local community outreach, and provision of boreholes and energy stoves.

Site characteristics

Bulindi (1°29′N, 31°28′E) is situated midway between the Budongo and Bugoma Central Forest Reserves in western Uganda, within the so-called Budongo-Bugoma corridor. Bulindi is unique in that it is a long-term chimpanzee research site located entirely on land belonging to local villagers (McLennan et al. 2020). The site is predominantly agricultural and village land, with remnant patches of unprotected and highly degraded riparian and swamp forest (McLennan & Plumptre 2012). The field site corresponds to the home range of one community of eastern chimpanzees. Other primate species found at the site include black and white colobus monkeys (Colobus guereza), tantalus monkeys (Chlorocebus tantalus), and blue monkeys (Cercopithecus mitis); olive baboons (Papio anubis) are transitory visitors.

Table 1. Basic site information for Bulindi Area

| Species | Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii |

| Area | 25 km² |

| Coordinates | 1.483333 , 31.466667 |

| Type of site | Non-protected area |

| Governance type | |

| Habitat type | Subtropical/tropical moist lowland forest, subtropical/tropical swamp forest, subtropical/tropical heavily degraded former forest, agricultural land |

Types of sites ⋅ Governance types ⋅ Habitat types

Ape status

Community size declined since the first period of research in 2006-2008, when an estimated 30 individuals or more were present (McLennan & Hill 2010): between 2012 (when all individuals were identified) and 2020 community size has numbered 18-22 individuals. The marked decline in community size between 2008 and 2012 is at least partially attributable to trappings (McLennan et al. 2012).

Table 2. Ape population estimates in Bulindi Area

| Species | Year | Occurrence | Encounter or visitation rate (nests/km; ind/day) | Density estimate [ind/ km²] (95% CI) | Abundance estimate (95% CI) | Survey area | Sampling method | Analytical framework | Source | Comments | A.P.E.S. database ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii | 2020 | Present | 22 | Bulindi Area (25 km²) | Full count | BCCP 2020 | Community size has varied between 18-22 individuals (2012-2020) |

Sampling methods ⋅ Analytical frameworks

Threats

More than 80% of the natural forest at Bulindi was converted to farmland in less than 10 years (McLennan et al. 2020). Rapid habitat loss and human encroachment has led to increased conflict between villagers and the resident chimpanzees; loss of wild foods has caused chimpanzees to forage daily for agricultural foods in croplands and around homes (McLennan 2013; McLennan et al. 2020). The chimpanzees are highly threatened by anthropogenic factors including ongoing habitat conversion, lethal crop protection measures (e.g. steel 'mantraps'; McLennan et al. 2012; Cibot et al. 2019a), a busy main road that divides their home range (McLennan & Asiimwe 2016), exposure to novel pathogens (McLennan et al. 2017, 2018) and anthropogenic stressors (McLennan et al. 2019a), and habitat loss reducing opportunities for female dispersal (McCarthy et al. 2020).

Table 3. Threats to apes in Bulindi Area

| Category | Specific threats | Threat level | Description | Year of threat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Residential & commercial development | Unknown | |||

| 2. Agriculture & aquaculture | 2.1 Annual & perennial non-timber crops | High | Between 2006 and 2014, 80% of forest in the chimpanzees' home range was cleared entirely for farming (McLennan et al. 2020). Agricultural expansion for both subsistence crops and cash crops such as sugarcane, tobacco, maize and rice (McLennan & Plumptre 2012; McLennan & Hill 2015). | 2012-Ongoing (2020) |

| 3. Energy production & mining | Unknown | |||

| 4. Transportation & service corridors | 4.1 Roads & railroads | High | A busy main road connecting Hoima and Masindi towns crosses the chimpanzee range. In 2017 the road was widened and tarmacked. The chimpanzees cross this road at times on a daily basis, putting them at risk of collision with vehicles (McLennan & Asiimwe 2016). One adult female chimpanzee, and her infant, were killed crossing the road during the period 2015-2020 (McLennan & Asiimwe 2016). | 2015-Ongoing (2020) |

| 5. Biological resource use | 5.3 Logging & wood harvesting | High | Unregulated commercial logging, i.e. local landowners sell trees to timber dealers, and then clear the land for farming (McLennan & Plumptre 2012). Residents also cut small trees for firewood. Most large trees were logged for timber between c. 2000-2015 (McLennan, unpubl. data). | 2000-Ongoing (2020) |

| 5. Biological resource use | 5.1.5 Persecution/human wildlife conflict | High | The chimpanzees are at high risk of potentially lethal crop protection measures, particularly large steel leg-hold traps (known as 'mantraps'). Mantraps are placed by agricultural fields by a minority of farmers to deter crop-foraging wildlife including wild pigs, monkeys and the chimpanzees (McLennan et al. 2012; Cibot et al. 2019a). At least 5 chimpanzees were caught in steel traps, 2007-2011 (McLennan et al. 2012). | 2007-Ongoing (2020) |

| 6. Human intrusion & disturbance | 6.3 Other human disturbances | High | High exposure to anthropogenic stressors including hostile interactions with local humans, roads, dogs, anthropogenic noise (McLennan et al. 2019a). Chimpanzee faecal glucocorticoid metabolite concentrations were substantially higher in chimpanzees in Bulindi compared to conspecifics in minimally-disturbed habitat in nearby Budongo Forest (McLennan et al. 2019a). | 2019-Ongoing (2020) |

| 7. Natural system modifications | 7.1 Fire & fire suppression | Medium | Fires used for clearing agricultural gardens threaten remaining forest areas during dry seasons. | Ongoing (2020) |

| 7. Natural system modifications | 7.3 Other ecosystem modifications | High | Reduced options for female dispersal caused by clearance of riparian forest corridors (McCarthy et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) |

| 8. Invasive & other problematic species, genes, diseases | 8.4 Pathogens | High | Chimpanzees in Bulindi have contact with waste of domestic animals and people. A number of potentially pathogenic intestinal parasites that may result from cross-species transmission have been detected in chimpanzees at Bulindi including enterobacteria such as Salmonella spp., enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Shigella spp./enteroinvasive E. coli (McLennan et al. 2018), among various nematode and protozoan parasites (Ota et al. 2015; McLennan et al. 2017). Respiratory diseases are also a threat (McLennan, unpubl. data). The chimpanzees exhibit an unusually high frequency of self-medication (whole leaf swallowing; McLennan & Huffman 2012; McLennan et al. 2017). | 2015-Ongoing (2020) |

| 9. Pollution | 9.3 Agricultural & forestry effluents | High | Local farmers commonly use inorganic herbicides and pesticides; potential impacts on the chimpanzees are not yet known. | Ongoing (2020) |

| 10. Geological Events | Absent | |||

| 11. Climate change & severe weather | Unknown | |||

| 12. Other options | Absent |

Conservation activities

The Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project (BCCP) was initiated in 2015 to help conserve the chimpanzees in Bulindi and their habitat, and provide livelihood support to local households. The project has since expanded to other regions within the Budongo-Bugoma corridor where chimpanzees survive in unprotected habitat around villages. Main project activities include supporting local residents through livelihood alternatives to deforestation, extensive tree planting, investing in children’s education, local community outreach, and provision of boreholes and energy stoves. These activities help reduce reliance on remaining natural forest and increase tolerance towards chimpanzees. In parallel, BCCP conducts long-term research and monitoring of multiple groups of 'village chimpanzees' (including the Bulindi community) to understand behavioral adaptations to human-driven environmental change, to aid targeted conservation efforts, and mitigate threats to the chimpanzees' welfare and survival (BCCP 2020).

Table 4. Conservation activities in Bulindi Area

| Category | Specific activity | Description | Implementing organization | Year of activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Development impact mitigation | 1.4 Farm more intensively and effectively in selected areas and spare more natural land | BCCP has a coffee growing alternative livelihood project. The project provides coffee seedlings to farmers and guidance on 'best practice' coffee farming. Unlike other cash crops (e.g. tobacco and rice), coffee is 'chimpanzee friendly' because farmers establish coffee in existing gardens rather than cutting new gardens in forest or wetlands, and chimpanzees and other primates do not eat any part of the coffee plant. Coffee matures after 2-3 years and the harvest can contribute significantly to household incomes (BCCP 2020). | Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project | Ongoing (2020) |

| 2. Counter-wildlife crime | 2.13 Provide sustainable alternative livelihoods; establish fish- or domestic meat farms | BCCP has an extensive tree planting program in Bulindi since 2015, including raising indigenous tree species for habitat enrichment, coffee as an alternative livelihood, and fast-growing timber species for sustainable household woodlots. The woodlots provide local households with an alternative source of wood and alternative income from timber sales, reducing reliance on remaining natural forest (BCCP 2020). | Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project | 2015-Ongoing (2020) |

| 3. Species health | 3.1 Wear face-masks to avoid transmission of viral and bacterial diseases to primates | Strict use of face masks and hand sanitisers by researchers and local 'Chimpanzee Monitors' entering forest areas, and when in proximity to chimpanzees; bespoke health and hygiene training provided to all staff (BCCP, unpublished data). | Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project | Ongoing (2020) |

| 4. Education & awareness | 4.1 Educate local communities about apes and sustainable use | BCCP provides conservation outreach for primary schoolchildren. The program aims to foster interest, empathy, and understanding of chimpanzees, interest in tree planting and awareness of importance of natural forest, and promotes 'safe' behavior for children encountering chimpanzees (BCCP 2020). | Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project | Ongoing (2020) |

| 5. Protection & restoration | 5.6 Habitat restoration | BCCP has an extensive tree planting program in Bulindi, including raising indigenous tree species for habitat enrichment and restoration since 2015 (BCCP 2020). | Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project | Ongoing (2020) |

| 6. Species management | Not reported | |||

| 7. Economic & other incentives | 7.1 Provide monetary benefits to local communities for sustainably managing their forest and its wildlife (e.g., REDD, alternative income, employment) | BCCP supports local households that own areas of natural forest used by the chimpanzees by sponsoring their children's education. Since inception in 2015, this school child sponsorship scheme has been instrumental in conserving remaining patches of riparian forest, following 2 decades of forest clearance in Bulindi (BCCP 2020). | Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project | 2015-Ongoing (2020) |

| 7. Economic & other incentives | 7.2 Provide non-monetary benefits to local communities for sustainably managing their forest and its wildlife (e.g., better education, infrastructure development) | The Bulindi Chimpanzee & Community Project (BCCP) was initiated in 2015 to help conserve the chimpanzees in Bulindi and their habitat, and provide livelihood support to local households. The project has since expanded to other regions in the Budongo-Bugoma corridor where chimpanzees survive in unprotected habitat around villages. Project activities include supporting local residents through livelihood alternatives to deforestation, extensive tree planting, investing in children’s education, and provision of boreholes and energy stoves, helping reduce reliance on remaining natural forest and increase tolerance of chimpanzees. In parallel, BCCP conducts long-term research and monitoring of the chimpanzees to understand adaptations to human-driven environmental change and mitigate threats to their welfare and survival (BCCP 2020). | Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project | 2015-Ongoing (2020) |

| 7. Economic & other incentives | 7.2 Provide non-monetary benefits to local communities for sustainably managing their forest and its wildlife (e.g., better education, infrastructure development) | In partnership with water charities (BridgIT, Drop4Drop and Suubi Community Projects–Uganda), BCCP constructs village boreholes (water wells) for local communities to improve health and quality of life by providing residents in chimpanzee areas with access to clean, safe water away from the forest. The wells reduce negative encounters between chimpanzees and people (often children) collecting water at forest streams. BCCP also constructs energy-saving stoves for residents, helping reduce household fuel consumption, alleviating pressure on chimpanzee habitat, while providing households with safer, more efficient cook stoves. | Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project, BridgIT, Drop4Drop, Suubi Community Projects Uganda | 2015-Ongoing (2020) |

| 8. Permanent presence | Not reported |

Conservation implementation challenges and enablers

Ongoing habitat conversion (clearance of riparian forest for agriculture) (McLennan & Plumptre 2012; McLennan & Hill 2015; McLennan et al. 2020). High levels of human-chimpanzee interactions including habitual feeding on agricultural crops by chimpanzees, frequent harassment of chimpanzees by local residents, occasional chimpanzee aggression towards humans, especially children (McLennan 2008; McLennan & Hill 2012, 2013). Human-human conflicts, i.e. differences between groups or individuals (e.g. local residents and conservation practitioners) about the management and conservation of chimpanzees; politicisation of chimpanzees by local politicians (McLennan & Hill 2013).

Table 5. Challenges reported for Bulindi Area

| Category | Challenge | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Site management | Not reported | ||

| 2. Resources & capacity | 2.3 General lack of funding | McLennan pers. comm. 2020 | |

| 3. Engaged community | Not reported | ||

| 4. Institutional support | 4.1 Lack of law enforcement | McLennan 2008 | Ongoing (2008) |

| 4. Institutional support | 4.3 Lack of protected area status | McLennan 2008 | Ongoing (2008) |

| 5. Ecological context | Not reported | ||

| 6. Safety & stability | Not reported |

Table 6. Enablers reported for Bulindi Area

| Category | Enabler | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Site management | Not reported | ||

| 2. Resources & capacity | Not reported | ||

| 3. Engaged community | Not reported | ||

| 4. Institutional support | Not reported | ||

| 5. Ecological context | Not reported | ||

| 6. Safety & stability | Not reported |

Research activities

Chimpanzees in Bulindi were first studied in 2006-2008. Research resumed in 2012 and continues to the present; since 2015 the chimpanzees are habituated. Research topics include: (1) chimpanzees dietary and behavioral responses to habitat loss, agricultural expansion and increased contact with humans, including crop feeding and human-chimpanzee interactions (e.g. McLennan & Hill 2010; McLennan 2013; McLennan & Hockings 2014; McLennan et al. 2019a, 2020); (2) attitudes towards chimpanzees among local residents and constraints to coexistence (e.g. McLennan & Hill 2012, 2013); (3) threats to chimpanzee survival (e.g. McLennan et al. 2012; McLennan & Asiimwe 2016; Cibot et al. 2019a); (4) health and disease (e.g. McLennan et al. 2017, 2018); (5) tool use (McLennan 2011a; McLennan et al. 2019b); and (6) paternity and reproductive success (Cibot et al. 2019b; McCarthy et al. 2020).

Documented behaviours

Table 7. Ape behaviors reported for Bulindi Area

| Behavior | Source |

|---|---|

| Crop feeding | McLennan 2013; McLennan et al. 2020 |

| Road crossing | McLennan & Asiimwe 2016 |

| Food sharing (agricultural crops) | McLennan et al. 2020 |

| Hunting animals without consumption | Cibot et al. 2017 |

| Self medication (leaf swallowing) | McLennan & Huffman 2012; McLennan et al. 2017 |

| Infant carrying by male chimpanzees | Cibot et al. 2019b |

| Honey digging with stick tools | McLennan 2011a; McLennan et al. 2019b |

| Hand-clasp grooming | McLennan 2011b |

| High male reproductive skew | McCarthy et al. 2020 |

| Chimpanzee-villager interactions (including human directed aggression) | McLennan & Hill 2010; McLennan 2010 |

| Tool-assisted extractive foraging | McLennan et al. 2019b |

| Foraging adaptations to forest loss | McLennan et al. 2020 |

| Nest tying | McLennan 2018 |

Exposure to climate change impacts

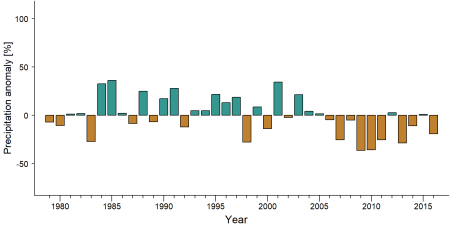

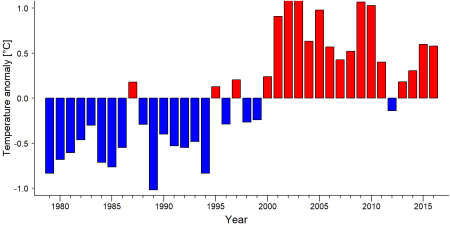

As part of a study on the exposure of African great ape sites to climate change impacts, Kiribou et al. (2024) extracted climate data and data on projected extreme climate impact events for the site. Climatological characteristics were derived from observation-based climate data provided by the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project ([ISIMIP www.isimip.org]). Parameters were calculated as the average across each 30-year period. For future projections, two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) were used. RCP 2.6 is a scenario with strong mitigation measures in which global temperatures would likely rise below 2°C. RCP 6.0 is a scenario with medium emissions in which global temperatures would likely rise up to 3°C by 2100. For the number of days with heavy precipitation events, the 98th percentile of all precipitation days (>1mm/d) was calculated for the 1979-2013 reference period as a threshold for a heavy precipitation event. Then, for each year, the number of days above that threshold was derived. The figures on temperature and precipitation anomaly show the deviation from the mean temperature and mean precipitation for the 1979-2013 reference period. The estimated exposure to future extreme climate impact events (crop failure, drought, river flood, wildfire, tropical cyclone, and heatwave) is based on a published dataset by Lange et al. 2020 derived from ISIMIP2b data. The same global climate models and RCPs as described above were used. Within each 30-year period, the number of years with an extreme event and the average proportion of the site affected were calculated (Kiribou et al. 2024).

Table 8. Estimated past and projected climatological characteristics in Bulindi Area

| 1981-2010 | 2021-2050, RCP 2.6 | 2021-2050, RCP 6.0 | 2071-2099, RCP 2.6 | 2071-2099, RCP 6.0 | |

| Mean temperature [°C] | 23.1 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 24.5 | 25.6 |

| Annual precipitation [mm] | 1245 | 1265 | 1332 | 1187 | 1451 |

| Max no. consecutive dry days (per year) | 25.2 | 25.5 | 30.4 | 27.6 | 28.5 |

| No. days with heavy precipitation (per year) | 5.9 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 8.4 |

Table 9. Projected exposure of apes to extreme climate impact events in Bulindi Area

| No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) | |

| Crop failure | 4 | 0.82 | 2 | 0.61 | 3 | 1.13 | 10 | 0.49 |

| Drought | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heatwave | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 50 |

| River flood | 1.25 | 0.59 | 4 | 2.46 | 1 | 0.66 | 5.25 | 3.51 |

| Tropical cyclone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wildfire | 30 | 2.26 | 30 | 1.91 | 29 | 1.57 | 29 | 1.37 |

External links

Bulindi Chimpanzee & Community Project website

Bulindi Chimpanzees Facebook

Bulindi Chimpanzees Instagram

Bulindi National Geographic

References

BCCP. (2020). 2019 Annual Report to Friends & Funders. Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project, Hoima, Uganda.

Cibot, M., Sabiiti, T., and McLennan, M.R. (2017). Two cases of chimpanzees interacting with dead animals without food consumption at Bulindi, Hoima District, Uganda. Pan Africa News, 24(1), 6–8. https://doi.org/10.5134/226632

Cibot, M., Le Roux, S., Rohen, J., & McLennan, M.R. (2019a). Death of a trapped chimpanzee: survival and conservation of great apes in unprotected agricultural areas of Uganda. African Primates, 13, 47–56.

Cibot, M., McCarthy, M. S., Lester, J. D., Vigilant, L., Sabiiti, T., & McLennan, M. R. (2019b). Infant carrying by a wild chimpanzee father at Bulindi, Uganda. Primates, 60(4), 333-338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-019-00726-z

McCarthy, M.S., Lester, J.D., Cibot, M., Vigilant, L., & McLennan, M.R. (2020). Atypically high reproductive skew in a small wild chimpanzee community in a human-dominated landscape. Folia Primatologica, 91(6), 688–696. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508609

McLennan, M.R. (2008). Beleaguered chimpanzees in the agricultural district of Hoima, western Uganda. Primate Conservation, 23, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1896/052.023.0105

McLennan, M.R. (2010). Case study of an unusual human–chimpanzee conflict at Bulindi, Uganda. Pan Africa News, 17(1), 1–4.

McLennan, M.R., & Hill, C.M. (2010). Chimpanzee responses to researchers in a disturbed forest–farm mosaic at Bulindi, western Uganda. American Journal of Primatology, 72, 907–908. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20839

McLennan, M. R. (2011a). Tool-use to obtain honey by chimpanzees at Bulindi: New record from Uganda. Primates, 52(4), 315-322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-011-0254-6

McLennan, M. R. (2011b). Preliminary observations of hand-clasp grooming by chimpanzees at Bulindi, Uganda. Pan Africa News, 18(2), 18–20.

McLennan, M. R. & Plumptre, A. J. (2012). Protected apes, unprotected forest: composition, structure and diversity of riverine forest fragments and their conservation value in Uganda. Tropical Conservation Science Vol. 5(1):79-103. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F194008291200500108

McLennan, M. R., Hyeroba, D., Asiimwe, C., Reynolds, V., & Wallis, J. (2012). Chimpanzees in mantraps: Lethal crop protection and conservation in Uganda. Oryx, 46(4), 598-603. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605312000592

McLennan, M. R. & Huffman, M. (2012). High Frequency of Leaf Swallowing and Its Relationship to Intestinal Parasite Expulsion in “Village” Chimpanzees at Bulindi, Uganda. American Journal of Primatology, 74, 642–650. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22017

McLennan, M.R. & Hill, C.M. (2012). Troublesome neighbours: Changing attitudes towards chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in a human-dominated landscape in Uganda. Journal for Nature Conservation, 20(4), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2012.03.002

McLennan, M.R. and Hill, C.M. (2013). Ethical issues in the study and conservation of an African great ape in an unprotected, human-dominated landscape in western Uganda. In: Ethics in the Field: Contemporary Challenges, ed. J. MacClancy and A. Fuentes. Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 42–66.

McLennan, M.R. (2013). Diet and feeding ecology of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in Bulindi, Uganda: foraging strategies at the forest–farm interface. International Journal of Primatology, 34(3), 585–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-013-9683-y

McLennan, M.R., Hockings, K.J. (2014). Wild chimpanzees show group differences in selection of agricultural crops. Scientific Reports, 4, 5956. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05956

McLennan, M.R. & Hill, C.M. (2015). Changing agricultural practices and human-chimpanzee interactions: tobacco and sugarcane farming in and around Bulindi, Uganda. In: State of the Apes. Volume II: Industrial Agriculture and Ape Conservation, ed. Arcus Foundation. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, pp. 29–31.

McLennan, M. R., & Asiimwe, C. (2016). Cars kill chimpanzees: case report of a wild chimpanzee killed on a road at Bulindi, Uganda. Primates, 57(3), 377-388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-016-0528-0

McLennan, M. R., Hasegawa, H., Bardi, M., & Huffman, M. A. (2017). Gastrointestinal parasite infections and self-medication in wild chimpanzees surviving in degraded forest fragments within an agricultural landscape mosaic in Uganda. PLOS ONE, 12(7), e0180431. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180431

McLennan, M. R., Mori, H., Mahittikorn, A., Prasertbun, R., Hagiwara, K., & Huffman, M. A. (2018). Zoonotic Enterobacterial Pathogens Detected in Wild Chimpanzees. EcoHealth, 15(1), 143-147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-017-1303-4

McLennan, M. R. (2018). Tie one on: ‘nest tying’ by wild chimpanzees at Bulindi—a variant of a universal great ape behavior?. Primates, 59(3), 227-233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-018-0658-7

McLennan, M. R., Howell, C. P., Bardi, M., & Heistermann, M. (2019a). Are human-dominated landscapes stressful for wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)? Biological Conservation, 233, 73-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.02.028

McLennan, M. R., Rohen, J., Satsias, Z., Sabiiti, T., Baruzaliire, J. M., & Cibot, M. (2019b). ‘Customary’use of stick tools by chimpanzees in Bulindi, Uganda: update and analysis of digging techniques from behavioural observations. Revue de primatologie,10, https://doi.org/10.4000/primatologie.6706

McLennan, M. R., Lorenti, G. A., Sabiiti, T., & Bardi, M. (2020). Forest fragments become farmland: dietary response of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) to fast‐changing anthropogenic landscapes. American Journal of Primatology, 82(4), e23090. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23090

Ota, N., Hasegawa, H., McLennan, M. R., Kooriyama, T., Sato, H., Pebsworth, P. A., & Huffman, M. A. (2015). Molecular identification of Oesophagostomum spp. from ‘village’ chimpanzees in Uganda and their phylogenetic relationship with those of other primates. Royal Society Open Science, 2(11), 150471.https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150471

Kiribou, R., Tehoda, P., Chukwu, O., Bempah, G., Kühl, H. S., Ferreira, J., ... & Heinicke, S. (2024). Exposure of African ape sites to climate change impacts. PLOS Climate, 3(2), e0000345.

Lange, S., Volkholz, J., Geiger, T., Zhao, F., Vega, I., Veldkamp, T., ... & Frieler, K. (2020). Projecting exposure to extreme climate impact events across six event categories and three spatial scales. Earth's Future, 8(12), e2020EF001616.

Page completed by: Matthew McLennan, Maureen McCarthy & Jack Lester Date: 04/01/2021