Sapo National Park

West Africa > Liberia > Sapo National Park

Français | Português | Bahasa Indonesia | Melayu

Summary

- Western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) are present in Sapo National Park.

- It has been estimated that 1,055 (CI: 595-1,870) individuals occur in the site.

- The chimpanzee population trend is stable.

- The park has a total size of 1,804 km².

- Key threats to chimpanzees are poaching and illegal mining.

- Conservation activities have focused on long-term bio-monitoring and law enforcement.

- Sapo National Park is Liberia's first protected area, established in 1983.

Site characteristics

Located in southeastern Liberia, Sapo National Park is Liberia's first protected area and represents one of the most intact forest ecosystems of the country (Tweh et al. 2018). The area of the park was extended from 1,304 km² to 1,804 km² in 2003 (Tweh et al. 2018). The park forms part of the Upper Guinean Forest ecosystem, and contains high levels of biodiversity (N'Goran et al. 2010). The park is a low elevation tropical humid rainforest. Elevation in the southeastern area is approximately 100 m with gently rolling hills while in the north, the elevation is approximately 400 m in the north with steep ridges (Peal & Kranz 1990). In addition to the western chimpanzee, other endangered and vulnerable species inhabit the site, including forest elephants (Loxodonta africana), pygmy hippopotamus (Hexaprotodon liberiensis), Jentink’s duiker (Cephalophus jentinki), red colobus (Piliocolobus badius), and Diana monkeys (Cercopithecus diana diana, N'Goran 2010).

Table 1. Basic site information for Sapo National Park

| Species | Pan troglodytes verus |

| Area | 1804 km² |

| Coordinates | 5.378432, -8.496117 |

| Type of site | Protected area (National Park) |

| Governance type | Governance by government |

| Habitat type | Subtropical/tropical moist lowland |

Types of sites ⋅ Governance types ⋅ Habitat types

Ape status

A survey in 1982 (one year before the establishment of the park), confirmed the presence of chimpanzees in the Sapo forest (Anderson et al. 1983). Based on the estimates from two surveys, one in 2009 (N'Goran et al. 2010) and a second one in 2017 (Tweh et al. 2018), the chimpanzee population in the park has remained relatively stable, with an estimated abundance of approximately 1,055 individuals.

Table 2. Ape population estimates in Sapo National Park

| Species | Year | Occurrence | Encounter or visitation rate (nests/km; ind/day) | Density estimate [ind/ km²] (95% CI) | Abundance estimate (95% CI) | Survey area | Sampling method | Analytical framework | Source | Comments | A.P.E.S. database ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan troglodytes verus | 1983 | Present | 0.24 | Southeastern sector (50 km²) | Line transects | Anderson et al. 1983 | Total survey effort: 42.7 km | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2002 | Present | Sapo National Park | Line transects | Waitkuwait 2003 | Assessment of Fauna & Flora International's bio-monitoring programme | |||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2007-2009 | Present | 0.27 | Sapo National Park, excluding southeast area | Line transects | Vogt 2011 | Fauna & Flora International bio-monitoring programme | ||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2009 | Present | 4.05 | 0.86 | 1079 (713-1633) | Sapo National Park, excluding mining areas | Line transects | N'Goran et al. 2010 | |||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2016-2017 | Present | 0.83 | 1055 (595-1870) | Sapo National Park, excluding southeast area | Line transects | Tweh et al. 2018 | Total survey effort: 38.38 km |

Sampling methods ⋅ Analytical frameworks

Threats

Sapo National Park has been primarily threatened by illegal hunting and mining (Tweh et al. 2018; Greengrass 2015; N'Goran et al. 2010). An estimated 18,000 illegal miners were inhabiting the park in 2010, the majority of which was evicted by the government in the same year (Vogt 2011). A survey of two commercial hunting camps bordering the park revealed high hunting pressure in the area, and the majority of bushmeat harvested was destined to urban areas (Greengrass 2015). The carcasses documented during this survey included chimpanzees as well as other endangered and vulnerable species, such as the red colobus monkey, Diana monkey, and pygmy hippopotamus. Furthermore, the development of the road network around the park is expected to increase hunting pressure and facilitate the bushmeat trade (Greengrass 2015), as well as other illegal activities in the park.

Table 3. Threats to apes in Sapo National Park

| Category | Specific threats | Threat level | Description | Year of threat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Residential & commercial development | 1.1 Housing & urban areas | High | Illegal settlement of miners; 18,000 settlers in 2010 (Vogt 2011). | 2010 |

| 2. Agriculture & aquaculture | 2.1 Annual & perennial non-timber crops | Present (severity unknown) | Present as a result of illegal settlements; scale unknown (N’Goran et al. 2010) | 2010-Ongoing (2023) |

| 3. Energy production & mining | 3.2.3 Artisanal mining | High | Illicit gold mining which has decreased since 2010 (Tweh et al. 2018); artisanal mining is still present (Junker personal. comm. 2019). | 2010-Ongoing (2019) |

| 4. Transportation & service corridors | 4.1 Roads & railroads | Present (severity unknown) | Development of the road network around the park facilitates illegal human activities in the park (Greengrass 2015). | 2015-Ongoing (2023) |

| 5. Biological resource use | 5.1.3 Commercial bushmeat trade | High | Poaching represents a major threat to chimpanzees and other species in the park (Tweh et al. 2018, N’Goran et al. 2010, Greengrass 2015), and most of the bushmeat is destined to urban areas (Greengrass 2015). Hunting sign encounter rate: 1.7/km (Tweh et al. 2018). | 2010-Ongoing (2023) |

| 6. Human intrusion & disturbance | 6.2 War, civil unrest & military exercises | High | Two civil wars since the establishment of the park disrupted conservation activities, and led to illegal occupation of the park, as well as poaching and extraction of natural resources (Greengrass 2015, Collen et al. 2011) | 1989-1996, 1999-2003 |

| 7. Natural system modifications | Unknown | |||

| 8. Invasive & other problematic species, genes, diseases | Unknown | |||

| 9. Pollution | Unknown | |||

| 10. Geological Events | Absent | |||

| 11. Climate change & severe weather | Unknown | |||

| 12. Other options | Absent |

Conservation activities

The Forestry Development Authority of Liberia is responsible for the sustainable management of the forest sector and the protection of all natural resources. It runs the Sapo National Park in collaboration with Fauna & Flora International (FFI) and Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (WCF). Main activities at the national park level include anti-poaching, conservation education awareness, and bio-monitoring & scientific research. As of 2019, the main activities in the research area have been camera trappings (2019,2020, 2021) by FFI and FDA in the entire national park. eDNA (focusing on Pygmy hippopotamus) was conducted in 2022. The national park forms part of the Tai-Grebo-Sapo Forest Complex, which is a conservation priority in West Africa. Conservation efforts in Sapo National Park have mainly focused on law enforcement, conservation awareness, and bio-monitoring. The WCF has supported Community Watch Teams (CWT), which comprise members from surrounding communities, and regularly patrol and support FDA rangers (WCF 2019). CWTs have played an important role in the eviction of illegal miners from the national park (WCF 2019). In 2012, Fauna & Flora International established a long-term bio-monitoring program to follow the population trends for chimpanzees, pygmy hippopotamuses, elephants, as well as duikers, birds, reptiles, and amphibians (Tweh et al. 2018). Together with Liberia's Forestry Development Authority, permanent transects are surveyed twice a year as part of this long-term bio-monitoring program (Tweh et al. 2018).

Table 4. Conservation activities in Sapo National Park

| Category | Specific activity | Description | Implementing organization | Year of activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Development impact mitigation | Not reported | |||

| 2. Counter-wildlife crime | 2.3 Conduct regular anti-poaching patrols | Community Watch Teams supported by the WCF regularly patrol the site (WCF 2019). | Wild Chimpanzee Foundation | 2019-Ongoing (2023) |

| 2. Counter-wildlife crime | 2.8 Provide training to anti-poaching ranger patrols | Members of the Community Watch Teams are trained in the use of equipment (GPS, compass, camera) and patrolling (WCF 2019). | Wild Chimpanzee Foundation | 2019-Ongoing (2023) |

| 2. Counter-wildlife crime | 2.11 Implement monitoring surveillance strategies (e.g., SMART) or use monitoring data to improve effectiveness of patrols | Long-term bio-monitoring of chimpanzee population (Tweh et al. 2018) | 2019-Ongoing (2023) | |

| 3. Species health | Not reported | |||

| 4. Education & awareness | 4.2 Involve local community in ape research and conservation management | As part of a long-term bio-monitoring program, staff of Liberia’s Forestry Development Authority and members of the local community are involved in the surveys (Tweh et al. 2018). | 2018-Ongoing (2023) | |

| 5. Protection & restoration | 5.2 Legally protect ape habitat | The area is designated as a National Park. | 1983-Ongoing (2023) | |

| 5. Protection & restoration | 5.9 Resettle illegal human communities (i.e., in a protected area) to another location | Eviction of 18,000 illegal settlers in the park by the Liberia's government (Vogt 2011). | 2010 | |

| 6. Species management | Not reported | |||

| 7. Economic & other incentives | Not reported | |||

| 8. Permanent presence | Not reported |

Conservation implementation challenges and enablers

The influx of local community dwellers inside the national park is hampering the SNP management to implement the protection of chimpanzees. Low manpower for conducting anti-poaching patrols in and outside the park has put chimpanzees under serious threat. Very high illiteracy among the rangers thus making it difficult to collect data, process court procedures, and conduct conservation education awareness to local community people.

Table 5. Challenges reported for Sapo National Park

| Category | Challenge | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Site management | 1.4 Conflict on land tenure | Tally, B. pers. comm. 2022 | Unknown |

| 2. Resources & capacity | 2.5 Lack of equipment/transportation | Waitkuwait 2003 | Unknown |

| 2. Resources & capacity | 2.2 Lack of staff | Tally, B. pers. comm. 2022 | Unknown |

| 3. Engaged community | Not reported | ||

| 4. Institutional support | 4.1 Lack of law enforcement | Greengrass 2015, N'Goran et al. 2010 | Unknown |

| 5. Ecological context | Not reported | ||

| 6. Safety & stability | Not reported |

Table 6. Enablers reported for Sapo National Park

| Category | Enabler | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Site management | Not reported | ||

| 2. Resources & capacity | Not reported | ||

| 3. Engaged community | Not reported | ||

| 4. Institutional support | Not reported | ||

| 5. Ecological context | Not reported | ||

| 6. Safety & stability | Not reported |

Research activities

Several surveys have been done in the park to monitor the chimpanzee population (e.g., N'Goran et al. 2010, Tweh et al. 2018), assess the impacts of conservation interventions (Tweh et al. 2018), investigate the behavior and ecology of chimpanzees in the park (Anderson et al. 1983), and investigate the impact of hunting pressure in the area (Greengrass 2015).

Documented behaviours

Table 7. Ape behaviors reported for Sapo National Park

| Behavior | Source |

|---|---|

| Nut cracking | Anderson et al. 1983 |

Exposure to climate change impacts

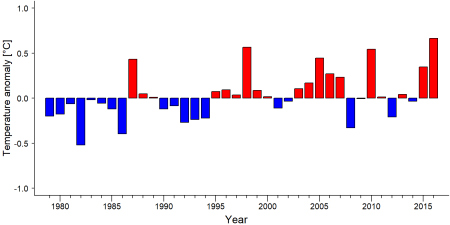

As part of a study on the exposure of African great ape sites to climate change impacts, Kiribou et al. (2024) extracted climate data and data on projected extreme climate impact events for the site. Climatological characteristics were derived from observation-based climate data provided by the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project ([ISIMIP www.isimip.org]). Parameters were calculated as the average across each 30-year period. For future projections, two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) were used. RCP 2.6 is a scenario with strong mitigation measures in which global temperatures would likely rise below 2°C. RCP 6.0 is a scenario with medium emissions in which global temperatures would likely rise up to 3°C by 2100. For the number of days with heavy precipitation events, the 98th percentile of all precipitation days (>1mm/d) was calculated for the 1979-2013 reference period as a threshold for a heavy precipitation event. Then, for each year, the number of days above that threshold was derived. The figures on temperature and precipitation anomaly show the deviation from the mean temperature and mean precipitation for the 1979-2013 reference period. The estimated exposure to future extreme climate impact events (crop failure, drought, river flood, wildfire, tropical cyclone, and heatwave) is based on a published dataset by Lange et al. 2020 derived from ISIMIP2b data. The same global climate models and RCPs as described above were used. Within each 30-year period, the number of years with an extreme event and the average proportion of the site affected were calculated (Kiribou et al. 2024).

Table 8. Estimated past and projected climatological characteristics in Sapo National Park

| 1981-2010 | 2021-2050, RCP 2.6 | 2021-2050, RCP 6.0 | 2071-2099, RCP 2.6 | 2071-2099, RCP 6.0 | |

| Mean temperature [°C] | 25.9 | 26.9 | 26.8 | 26.9 | 28 |

| Annual precipitation [mm] | 2893 | 2882 | 3001 | 2921 | 2958 |

| Max no. consecutive dry days (per year) | 17.5 | 21 | 16.9 | 20.4 | 19.1 |

| No. days with heavy precipitation (per year) | 5.9 | 12.5 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 15.6 |

Table 9. Projected exposure of apes to extreme climate impact events in Sapo National Park

| No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) | |

| Crop failure | 2 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.04 | 6 | 0.04 |

| Drought | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heatwave | 13 | 100 | 10.5 | 100 | 17.5 | 100 | 15 | 100 |

| River flood | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 0.92 | 0.5 | 0.08 |

| Tropical cyclone | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.36 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Wildfire | 30 | 0.44 | 30 | 0.38 | 29 | 0.46 | 29 | 0.41 |

References

Kiribou, R., Tehoda, P., Chukwu, O., Bempah, G., Kühl, H. S., Ferreira, J., ... & Heinicke, S. (2024). Exposure of African ape sites to climate change impacts. PLOS Climate, 3(2), e0000345.

Lange, S., Volkholz, J., Geiger, T., Zhao, F., Vega, I., Veldkamp, T., ... & Frieler, K. (2020). Projecting exposure to extreme climate impact events across six event categories and three spatial scales. Earth's Future, 8(12), e2020EF001616.

Tweh, C., Kouakou, C.Y., Chira, R., Freeman, B., Githaiga, J.M., Kerwillain, S., Molokwu-Odozi, M., Varney M. and Junker, J. 2018. Nest counts reveal a stable chimpanzee population in Sapo National Park, Liberia. Primate Conservation 2018 (32): 12 pp.

N’Goran, K. P., Kouakou, C.Y. and Herbinger I. 2010. Report on the Population Survey and Monitoring of Chimpanzee in Sapo National Park, Liberia (June–December 2009). Report. Wild Chimpanzee Foundation, Abidjan, Côted’Ivoire.

Anderson, R., Williamson, E.A., and Carter, J. 1983. Chimpanzees of Sapo Forest, Liberia: density, nests, tools and meat-eating. PRIMAaXS, 24(4): 594-601.

Waitkuwait, W.E. 2003. Report on the First Year of Operation of a Community-based Bio-monitoring Programme in and around Sapo National Park, Sinoe County, Liberia. Report. Fauna and Flora International.

Vogt, M. 2011. Results of Sapo National Park Bio-Monitoring Programme 2007-2009. Report. Fauna & Flora International, Monrovia, Liberia.

Greengrass, E. 2015. Commercial hunting to supply urban markets threatens mammalian biodiversity in Sapo National Park. Oryx 50(3), 397–404.

Collen, B., Howard, B., Konie, J., Daniel, O., and Rist, J. 2011. Field surveys for the endangered pygmy hippopotamus Choerpsis liberiensis in Sapo National Park, Liberia. Oryx, 45(1), 35–37.

Wild Chimpanzee Foundation. 2019. Activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa. Annual Report 2018.

Peal, A. L., & Kranz, K. R. (1990). Antelopes: GLobal Survey and Regional Action Plans, Part 3. West and

Central Africa. Gland, Switzerland: World Conservation Union.

Page completed by: Ben Tally & A.P.E.S. Wiki Team Date: 23/01/23