Bafing

West Africa > Mali > Bafing

Summary

- Western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) are present in Bafing.

- It has been estimated that between 417-1,408 individuals occurred in the site in 1993.

- The chimpanzee population trend is unknown.

- This site has a total size of 5000 km².

- Key threats to chimpanzees is habitat degradation due to subsistence farming.

- No conservation activities were reported for Bafing.

- Hottest and driest place in which western chimpanzees exist. Chimpanzees do not seem to be restricted to riverine forest, but are spread widely through woodland.

Site characteristics

Bafing is situated in southern Mali. The current status of the site is not known. This site is 5000 km² (World Database on Protected Areas 2019). Woodlands dominate most of the landscape. During his survey of south-western Mali, Moore (1985) regularly observed buffalo Syncerus caffer, roan Hippotragus equinus, hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus, and warthog Phacochoerus africanus. Sayer (1977) encountered giant eland Tragelaphus derbianus and giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis in this area. Lion Panthera leo, leopard Panthera pardus, and African wild dog Lycaon pictus also probably occur at very low densities (Moore 1985). The current state of biodiversity is not known. Although this is the hottest and driest place in which western chimpanzees are known to exist (Kortlandt 1983), chimpanzees at this site do not seem to be restricted to riverine forest, but are spread widely through the woodland (Moore 1985).

Table 1. Basic site information for Bafing

| Area | 5000 km² |

| Coordinates | 12.90, -10.58 |

| Designation | Unknown |

| Habitat types | Inland Rocky Areas, Subtropical/Tropical Dry Lowland Grassland, Subtropical/Tropical Dry Forest |

IUCN habitat categories Site designations

Ape status

In the 1970’s and 80’s, surveys conducted from vehicles or on foot confirmed chimpanzee presence in this area and estimated chimpanzee density at 0.08 chimpanzees per km2, resulting in a population of several hundred chimpanzees for the site (Sayer 1977, Moore 1985). More recent surveys by Pavy (1993) and Granier and Martinez (2004) estimated chimpanzee density at 0.27 and 0.35-0.4, respectively, yielding a population closer to, or above 1,000 individuals.

Table 2. Great ape population estimates in Bafing

| Species | Year | Abundance estimate (95% CI) | Density estimate [ind./ km²] (95% CI) | Encounter rate (nests/km) | Area | Method | Source | Comments | A.P.E.S. database ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan troglodytes verus | 1972-1974 | Present | Parc National du Baoulé and its three adjacent reserves of Fina, Badinnko and Kongossombougou, and the surrounding controlled hunting areas; study area size: 10,000 km² | Index survey | Sayer 1977 | Reconnaissance walk | |||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 1984 | 700 | 0.08 | South-west Mali; study area size: 5,000 km² | Index survey | Moore 1985 | Survey effort road: 650 km; survey effort foot: 100 km; extrapolation based on similar habitat types | ||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 1993 | 1,408 | 0.27 | Bafing; study area size: 5,200 km² | Informed guess | Pavy 1993, in Kormos et al. 2003 | Results of a “nest survey” were extrapolated to probable chimpanzee habitat | ||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2003- 2004 | 0.35-0.4 | 6.5 | Area near camps Fari, Faragama, Djakoli | Line transect (Distance) | Granier & Martinez 2004 | Survey effort: 29 km on 18 line transects; 190 nests observed | ||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2004 | Present | Area around Solo village in Bafing; study area size: 183 km² | Index survey | Duvall 2008 | Duvall (2008) walked loops of 62 km twice weekly for several months, encountered chimpanzee groups directly (48) or indirectly (224) on 272 occasions (Duvall 2008) |

Threats

Populations of several other species of large wild animals in Mali have declined drastically (Sayer 1977, Moore 1985), and it therefore seems probable that Mali’s chimpanzee population has also declined, although there is no information on demographic trends to prove this (Kormos et al. 2003). The main causes of this population decline are hunting and agricultural expansion (Kormos et al. 2003), but road construction, human settlement, mining, and natural system modification causing flooding (Moor 1985, Kormos et al. 2003) are additional threats to chimpanzees and other wildlife species in this area.

Table 3. Threats to great apes in Bafing

| Category | Specific threats | Threat level | Quantified severity | Description | Year of threat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Residential & commercial development | 1.1 Housing & urban areas | Medium | Settlement and agriculture are allowed inside the parks and reserves in Mali (Sayer 1977, Duvall 2008) | Ongoing (2008) | |

| 2. Agriculture & aquaculture | 2.3 Livestock farming & ranching | High | Settlement and agriculture are allowed inside the parks and reserves in Mali (Sayer 1977) | 1977-2000 | |

| 3. Energy production & mining | 3.2 Mining & quarrying | Medium | Gold-mining near Kéniéba and Sadiola (Caspary et al. 1998, in Kormos et al. 2003) | Ongoing (2003) | |

| 4. Transportation & service corridors | 4.1 Roads & railroads | Medium | Proposed road connecting Bamako and Dakar passing through Kouroukoto (Kormos et al. 2003) | Ongoing (2003) | |

| 5. Biological resource use | 5.1 Hunting & collecting terrestrial animals | Present | The killing of chimpanzees to protect crops and wild fruit trees has been reported for parts of Mali (Duvall 2008, Moore 1985, Sayer 1977), in other areas there are taboos against hunting chimpanzees (Terrade pers. obs.) | Ongoing (2008) | |

| 6. Human intrusions & disturbance | Unknown | ||||

| 7. Natural system modifications | 7.2 Dams & water management/use | High | A large dam constructed on Bafing river at Manantali flooding some 500 km2 (Moore 1985) | 1990 | |

| 8. Invasive & other problematic species, genes, diseases | Unknown | ||||

| 9. Pollution | 9.3 Agricultural & forestry effluents | Low | Area to be freed from onchocerciasis and trypanosomiasis; programmes to eliminate the vectors of the diseases are scheduled to take 20 years to complete (Sayer 1977). | 1977-1997 | |

| 10. Geological Events | Absent | ||||

| 11. Climate change & severe weather | Unknown | ||||

| 12. Other options | Absent |

Conservation activities

Table 4. Conservation activities in Bafing

| Category | Specific activity | Description | Year of activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Residential & commercial development | Not reported | ||

| 2. Agriculture & aquaculture | Not reported | ||

| 3. Energy production & mining | Not reported | ||

| 4. Transportation & service corridors | Not reported | ||

| 5. Biological resource use | Not reported | ||

| 6. Human intrusions & disturbance | Not reported | ||

| 7. Natural system modifications | Not reported | ||

| 8. Invasive & other problematic species, genes, diseases | Not reported | ||

| 9. Pollution | Not reported | ||

| 10. Education & Awareness | Not reported | ||

| 11. Habitat Protection | Not reported | ||

| 12. Species Management | Not reported | ||

| 13. Livelihood; Economic & Other Incentives | Not reported |

Conservation activities list (Junker et al. 2017)

Challenges

Table 5. Challenges reported for Bafing

| Challenge | Source |

|---|---|

| Not reported |

Research activities

Documented behaviors

Table 6. Great ape behaviors reported for Bafing

| Behavior | Source |

|---|---|

| Honey eating | Kühl et al. 2019 |

| Termite fishing | Kühl et al. 2019 |

| Termite eating | Kühl et al. 2019 |

Exposure to climate change impacts

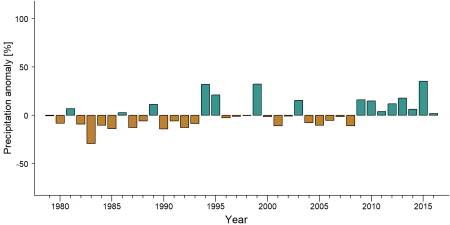

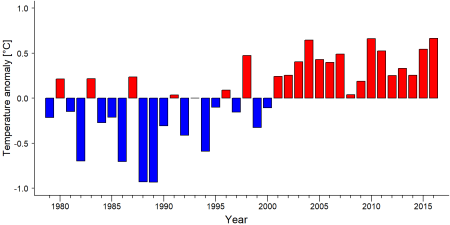

As part of a study on the exposure of African great ape sites to climate change impacts, Kiribou et al. (2024) extracted climate data and data on projected extreme climate impact events for the site. Climatological characteristics were derived from observation-based climate data provided by the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP, www.isimip.org). Parameters were calculated as the average across each 30-year period. For 1981-2010, the EWEMBI dataset from ISIMIP2a was used. For the two future periods (2021-2050 and 2071-2099) ISIMIP2b climate data based on four CMIP5 global climate models were used. For future projections, two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) were used. RCP 2.6 is a scenario with strong mitigation measures in which global temperatures would likely rise below 2°C. RCP 6.0 is a scenario with medium emissions in which global temperatures would likely rise up to 3°C by 2100. For the number of days with heavy precipitation events, the 98th percentile of all precipitation days (>1mm/d) was calculated for the 1979-2013 reference period as a threshold for a heavy precipitation event. Then, for each year, the number of days above that threshold was derived. The figures on temperature and precipitation anomaly show the deviation from the mean temperature and mean precipitation for the 1979-2013 reference period. The estimated exposure to future extreme climate impact events (crop failure, drought, river flood, wildfire, tropical cyclone, and heatwave) is based on a published dataset by Lange et al. 2020 derived from ISIMIP2b data. The same global climate models and RCPs as described above were used. Within each 30-year period, the number of years with an extreme event and the average proportion of the site affected were calculated (Kiribou et al. 2024).

Table 7. Estimated past and projected climatological characteristics in Bafing

| 1981-2010 | 2021-2050, RCP 2.6 | 2021-2050, RCP 6.0 | 2071-2099, RCP 2.6 | 2071-2099, RCP 6.0 | |

| Mean temperature [°C] | 28 | 29.2 | 29.1 | 29.5 | 30.9 |

| Annual precipitation [mm] | 1083 | 1099 | 1058 | 1045 | 985 |

| Max no. consecutive dry days (per year) | 112.4 | 111.1 | 119 | 116.1 | 119.7 |

| No. days with heavy precipitation (per year) | 2.6 | 4 | 4 | 3.9 | 3 |

Table 8. Projected exposure of apes to extreme climate impact events in Bafing

| No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) | |

| Crop failure | 6 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 4.5 | 0.01 | 11 | 0.01 |

| Drought | 1 | 50 | 1 | 75 | 0.25 | 25 | 2.25 | 100 |

| Heatwave | 0.5 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 50 |

| River flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.02 |

| Tropical cyclone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wildfire | 30 | 1.09 | 30 | 1.06 | 29 | 0.97 | 29 | 1.28 |

References

Duvall C S. 2008. Human settlement ecology and chimpanzee habitat selection in Mali. Landscape Ecology 23: 699-716.

Granier N., Martinez L. 2004. Première reconnaissance des chimpanzés Pan troglodytes verus dans la zone transfontalière entre la Gunée et le Mali (Afrique de l’Ouest). Primatologie 6: 423-447.

Kiribou, R., Tehoda, P., Chukwu, O., Bempah, G., Kühl, H. S., Ferreira, J., ... & Heinicke, S. (2024). Exposure of African ape sites to climate change impacts. PLOS Climate, 3(2), e0000345.

Kormos R, Boesch C, Bakarr M I, Butynski T. (eds.). 2003. West African Chimpanzees. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group. IUCN, Switzerland and UK.

Kortlandt A 1983. Marginal habitats of chimpanzees. Journal of Human Evolution: 12 231–278.

Kühl H S, Boesch C, Kulik L, Hass F, Arandjelovic M, Dieguez P, et al. 2019. Human impact erodes chimpanzee behavioral diversity. Science 363: 1453–1455.

Moore J J. 1985. Chimpanzee survey in Mali, West Africa. Primate Conservation 6: 59–63.

Sayer J A. 1977. Conservation of large mammals in the Republic of Mali. Biological Conservation 12: 245–263.

Page completed by: A.P.E.S. Wiki Team & E. Terrade Date: 18/11/2019