Banco National Park

West Africa > Côte d'Ivoire > Banco National Park

Français | Português | Español | Bahasa Indonesia | Melayu

Summary

- Western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) are present in Banco National Park.

- It has been estimated that around 26 individuals occur in the site.

- The chimpanzee population trend is stable.

- The site has a total size of 34 km².

- Key threats to chimpanzees are pollution, hunting, and pressure from urban surroundings.

- Conservation activities have focused on conservation and environmental awareness campaigns and education.

- The site is surrounded by the capital city of Abidjan.

Site characteristics

The Banco National Park was created in October 1953. It is located in the heart of the Ivorian economic capital, Abidjan, and is bounded by the municipalities of Adjamé, Attécoubé, Abobo, and Yopougon. The surface of the park has shrunk over the years and now covers an area of 3,438 hectares. Being the unique remaining relic of the dense primary forest that once covered the area of Abidjan, Banco National Park is often described as the hydraulic reservoir and green lung of the economic capital of Côte d'Ivoire. This protected area is a center for environmental education (OIPR n.d.). The park holds about 600 ha of primary forests; an arboretum of over 800 species of higher plants native to the tropics of Africa, Asia and Latin America; many fish ponds located in the heart of the park, a semi-natural swimming pool, an ecomuseum, and the presence of a family of chimpanzees (OIPR n.d.).

Table 1. Basic site information for Banco National Park

| Species | 'Pan troglodytes verus |

| Area | 34 km² |

| Coordinates | Lat: 5.395175 , Lon: -4.052743 |

| Type of site | Protected area (National Park) |

| Habitat types | Subtropical/tropical dry forest, Subtropical/tropical moist lowland forest, Subtropical/tropical heavily degraded former forest, Agricultural land, Urban areas, Wetlands (lakes, rivers, streams, bogs, marshes), Artificial aquatic (water storage) |

| Type of governance |

IUCN habitat categories Site designations

Ape status

A marked nest count study conducted in the Banco National Park in 2006 confirmed the presence of a small chimpanzee population. Twentysix fresh nests (including single nests and a group of up to 5 nests) were found along transects, and 5 off transects. The population was estimated to be around 20 individuals. In 2006, assistants succeeded several times to directly observe chimpanzees in groups of over ten individuals (WCF n.d.). Visitors of the park sighted ca. 20 chimpanzees in 2013 (Normand, E., personal communication). The manager of the park supports a group of up to 40 chimpanzees, and 3-4 isolated individuals are occasionally seen in the park (Bakayoko, H, pers. com). Based on these corroborating statements, the population of chimpanzees within the site is likely stable or increasing.

Table 2. Ape population estimates reported for Banco National Park

| Species | Year | Occurrence | Encounter or vistation rate (nests/km; ind/day) | Density estimate [ind./ km²] (95% CI) | Abundance estimate (95% CI) | Survey area | Sampling method | Analytical framework | Source | Comments | A.P.E.S. database ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2006 | 0.22 | 7 (4-14) | Banco National Park | Line transects | WCF 2009 | |||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2013 | 20 | Banco National Park | Informed guess | Normand, E. personal comm., 2016 | ||||||

| Pan troglodytes verus | 2021 | 40-50 | Banco National Park | Informed guess | Bakayoko, Hillihase, personal comm. 2021 |

Threats

Banco National Park is highly threatened by the neighboring populations, which exert a high pressure on the fauna and flora of the park. Snares are regularly found and poachers caught, illustrating that poaching is very much present within the park. Pollution is a real challenge for the park. The different types of pollution caused by domestic, artisanal, or industrial discharges destroy trees and pollute the land over an average distance of 200 m around the sources of pollution (Kouadio & Singh 2020).

Table 3. Threats to apes reported for Banco National Park

| Category | Specific threats | Threat level | Description | Year of threat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 Geological events | Absent | |||

| 12 Other threat | Absent | |||

| 5 Biological resource use | 5.1 Hunting & collecting terrestrial animals | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 5 Biological resource use | 5.2 Gathering terrestrial plants | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 5 Biological resource use | 5.3 Logging & wood harvesting | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 9 Pollution | 9.1 Domestic & urban waste water | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 9 Pollution | 9.6 Energy emissions | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 6 Human intrusions & disturbance | 6.1 Recreational activities | Low (up to 30% of population affected) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 1 Residential & commercial development | 1.1 Residential areas | Medium (30-70% of population affected) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 9 Pollution | 9.4 Garbage & solid waste | Medium (30-70% of population affected) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 1 Residential & commercial development | 1.2 Commercial & industrial areas | Present (unknown severity) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 2 Agriculture & aquaculture | 2.1 Annual & perennial non-timber crops | Present (unknown severity) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | 8.1 Invasive non-native/alien species | Present (unknown severity) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 9 Pollution | 9.2 Industrial & military effluents | Present (unknown severity) | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 3 Energy production & mining | Unknown | |||

| 4 Transportation & service corridors | Unknown | |||

| 7 Natural system modifications | Unknown | |||

| 11 Climate change & severe weather | Unknown |

Conservation activities

The Banco NP has become a hotspot for education and awareness campaigns for environment conservation in Abidjan. Many NGO regularly organize popular events within the park involving kids, neighboring communities, students, etc.

Table 4. Conservation activities reported for Banco National Park

| Category | Specific activity | Description | Implementing organization(s) | Year of activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Counter-wildlife crime | 2.3 Conduct regular anti-poaching patrols | Ongoing (2021) | ||

| 2 Counter-wildlife crime | 2.6 Regularly de-activate/remove ground snares | Ongoing (2021) | ||

| 4 Education & awareness | 4.1 Educate local communities about apes and sustainable use | Ongoing (2021) | ||

| 4 Education & awareness | 4.2 Involve local community in ape research and conservation management | Ongoing (2021) | ||

| 4 Education & awareness | 4.5 Implement multimedia campaigns using theatre, film, print media, discussions | Ongoing (2021) | ||

| 5 Protection & restoration | 5.2 Legally protect ape habitat | Ongoing (2024) |

Conservation activities list (Junker et al. 2017)

Challenges

Table 5. Challenges reported for Banco National Park

| Challenges | Specific challenges | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Site management | 1.2 Need for improved coordination | OIPR n.d. | |

| 4 Institutional support | 4.2 Lack of government support | OIPR n.d. | |

| Other (Strong urban pressure) | OIPR n.d. |

Enablers

Table 6. Enablers reported for Banco National Park

| Enablers | Specific enablers | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Site management | |||

| 2 Resources and capacity | |||

| 3 Engaged community | |||

| 4 Institutional support | |||

| 5 Ecological context | |||

| 6 Safety and stability |

Research activities

Documented behaviours

Table 7. Behaviours documented for Banco National Park

| Behavior | Source |

|---|---|

| Not reported |

Exposure to climate change impacts

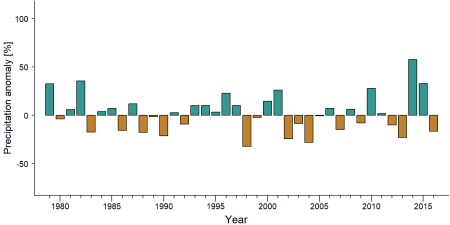

As part of a study on the exposure of African great ape sites to climate change impacts, Kiribou et al. (2024) extracted climate data and data on projected extreme climate impact events for the site. Climatological characteristics were derived from observation-based climate data provided by the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP, www.isimip.org). Parameters were calculated as the average across each 30-year period. For 1981-2010, the EWEMBI dataset from ISIMIP2a was used. For the two future periods (2021-2050 and 2071-2099) ISIMIP2b climate data based on four CMIP5 global climate models were used. For future projections, two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) were used. RCP 2.6 is a scenario with strong mitigation measures in which global temperatures would likely rise below 2°C. RCP 6.0 is a scenario with medium emissions in which global temperatures would likely rise up to 3°C by 2100. For the number of days with heavy precipitation events, the 98th percentile of all precipitation days (>1mm/d) was calculated for the 1979-2013 reference period as a threshold for a heavy precipitation event. Then, for each year, the number of days above that threshold was derived. The figures on temperature and precipitation anomaly show the deviation from the mean temperature and mean precipitation for the 1979-2013 reference period.

The estimated exposure to future extreme climate impact events (crop failure, drought, river flood, wildfire, tropical cyclone, and heatwave) is based on a published dataset by Lange et al. 2020 derived from ISIMIP2b data. The same global climate models and RCPs as described above were used. Within each 30-year period, the number of years with an extreme event and the average proportion of the site affected were calculated (Kiribou et al. 2024).

Table 8. Estimated past and projected climatological characteristics in Banco National Park

| Value | 1981-2010 | 2021-2050, RCP 2.6 | 2021-2050, RCP 6.0 | 2071-2099, RCP 2.6 | 2071-2099, RCP 6.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean temperature [°C] | 27 | 28 | 27.9 | 28.1 | 29.1 |

| Annual precipitation [mm] | 1821 | 1714 | 1802 | 1745 | 1830 |

| Max no. consecutive dry days (per year) | 28.9 | 24.5 | 26 | 25.3 | 30.2 |

| No. days with heavy precipitation (per year) | 7 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 7.6 |

Table 9. Projected exposure of apes to extreme climate impact events in Banco National Park

| Type | No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2021-2050, RCP 6.0) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 2.6) | No. of years with event (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) | % of site exposed (2070-2099, RCP 6.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop failure | 1.5 | 0.14 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.72 |

| Drought | 0.25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heatwave | 14.5 | 100 | 15.5 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 17 | 100 |

| River flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0 |

| Tropical cyclone | 0.5 | 0.44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wildfire | 30 | 0.43 | 30 | 0.4 | 29 | 0.43 | 29 | 0.4 |

External links

Relevant datasets

References

Akaffou, S.V.E, Abrou, N.E.J&M.S. Tiébré (2020). Current and future distribution of Chromolaena odorata(L.) R.M. King & H. Roxb (Compositae) and Hopea odorata Roxb (Dipterocarpaceae) in the Banco national park. IOSR Journal Of Pharmacy And Biological Sciences (IOSR-JPBS) e-ISSN:2278-3008, p-ISSN:2319-7676. Volume 15, Issue 2 Ser. III (Mar –Apr 2020), PP 06-14

Bitty, EA, Kadjo B., Gonedele Bi, S. Okon, M.O.and Kouassi, K.P. et al. (2013) Inventaire de la faune mammalogique d’une forêt urbaine, le Parc National du Banco, Côte d’Ivoire. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 7(4): 1678-1687

Kouadio, K. I., & Singh, R. Urban Forest BNP in Abidjan.International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET). https://www.ijraset.com/fileserve.php?FID=32326

Kiribou, R., Tehoda, P., Chukwu, O., Bempah, G., Kühl, H. S., Ferreira, J., ... & Heinicke, S. (2024). Exposure of African ape sites to climate change impacts. PLOS Climate, 3(2), e0000345.

OIPR (2021). https://www.oipr.ci/index.php/parcs-reserves/parcs-nationaux/parc-national-du-banco (Accessed, 19.01.2021)

Page created by: Tene Sop Date: NA