Gombe National Park

East Africa > Tanzania > Gombe National Park

Français | Português | Español | Bahasa Indonesia | Melayu

Summary

- Eastern chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) are present in Gombe National Park.

- Approximately 90 individuals occur in the site.

- The chimpanzee population trend is stable.

- The site has a total size of 35 km².

- Key threats to chimpanzees are diseases, forest loss and loss of forest connectivity.

- Conservation activities have focused on long-term research, education and awareness raising.

- Jane Goodall began studying the chimpanzees at the site in 1960, when little was known about the behavior and social structure of wild chimpanzees

Site characteristics

Located along the eastern edge of Lake Tanganyika in eastern Tanzania, Gombe National Park covers an area of 35 sq. km of mountainous terrain (Weiss et al. 2017). The site encompasses a mosaic of habitats and their transitions, from riverine forest to deciduous woodland and grassland (Weiss et al. 2017). Although the park covers a small area, it is rich in biodiversity. In addition to chimpanzees, several other primates inhabit the site, including olive baboons (Papio anubis), red colobus monkeys (Piliocolobus tephrosceles), red-tailed monkeys (Cercopithecus ascanius schmidti), blue monkeys (Cercopithecus mitis doggetti), and vervets (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) (Lonsdorf et al. 2021). The site was first established as the Gombe Stream Game Reserve in 1943, and upgraded to national park in 1968. As part of an effort to recognize that the national park is part of a larger ecosystem that needs to be integrated into conservation efforts, the geographical area known as the Greater Gombe Ecosystem was defined as part of the Conservation Action Planning process in 2005 (Wilson et al. 2020). Jane Goodall began studying the chimpanzees at the site in 1960, when little was known about the behavior and social structure of wild chimpanzees (Pusey et al. 2007). During her first year of study she made the key discoveries that chimpanzees make and use tools (Goodall 1964) and hunt and eat meat (Goodall 1963).

Table 1. Basic site information for Gombe National Park

| Species | 'Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii |

| Area | 35 km² |

| Coordinates | Lat: -4.698600 , Lon: 29.644148 |

| Type of site | Protected area (National Park) |

| Habitat types | Subtropical/tropical moist montane forest, Grassland |

| Type of governance |

IUCN habitat categories Site designations

Ape status

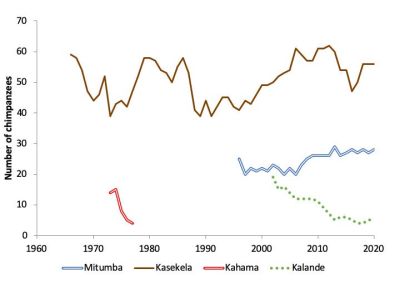

Gombe contains three communities of chimpanzees: Mitumba, Kasekela and Kalande. The chimpanzee population in the park decreased over time from an estimated 120–150 individuals in the 1960s to approximately 90 individuals in 2020 (Wilson et al. 2020). However, the consistent presence of approximately 90 chimpanzees since 2002 suggests that the population might be stable (Wilson et al. 2020).

Table 2. Ape population estimates reported for Gombe National Park

| Species | Year | Occurrence | Encounter or vistation rate (nests/km; ind/day) | Density estimate [ind./ km²] (95% CI) | Abundance estimate (95% CI) | Survey area | Sampling method | Analytical framework | Source | Comments | A.P.E.S. database ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii | 2020 | 89-92 | Gombe National Park, entire area | Full count, Genetic (dung/hair) | Wilson et al. 2020 |

Threats

Due to the small size of the park and its small and relatively isolated chimpanzee population, chimpanzees at the site are particularly vulnerable to diseases and habitat encroachment (Wilson et al. 2020). Although diseases occur naturally, human activities can increase the risk of transmission to apes. Furthermore, respiratory disease appears to be the most common cause of death for Gombe chimpanzees, with 48% of chimpanzees inferred to have died from illness reported to exhibit respiratory symptoms (Wilson et al. 2020).

Table 3. Threats to apes reported for Gombe National Park

| Category | Specific threats | Threat level | Description | Year of threat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Residential & commercial development | Absent | |||

| 3 Energy production & mining | Absent | |||

| 4 Transportation & service corridors | Absent | |||

| 10 Geological events | Absent | |||

| 2 Agriculture & aquaculture | 2.1 Annual & perennial non-timber crops | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Smallholder agriculture; increase in smallholder oil palm cultivation (Langat 2019). | Ongoing (2019) |

| 5 Biological resource use | 5.3 Logging & wood harvesting | High (more than 70% of population affected) | As early as the 1940s, deforestation fueled by growing human populations threatened this area (Pusey et al. 2007). Charcoal production is an ongoing threat (Langat 2019). | Ongoing (2019) |

| 8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | 8.2 Problematic native species | High (more than 70% of population affected) | Diseases occurring naturally in the chimpanzee population (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) |

| 8 Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | 8.4 Pathogens | High (more than 70% of population affected) | High risk of acquiring diseases from humans (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) |

| 5 Biological resource use | 5.1 Hunting & collecting terrestrial animals | Low (up to 30% of population affected) | Few cases of poaching (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) |

| 12 Other threat | 12.1 Other threat | Low (up to 30% of population affected) | A few cases of chimpanzee killings by humans have been reported in the park as retaliation due to crop raiding (TAWIRI 2018). | Ongoing (2018) |

| 12 Other threat | 12.1 Other threat | Present (unknown severity) | The connectivity between Gombe National Park and Masito Ugalla is under threat from forest conversion (TAWIRI 2018). | Ongoing (2018) |

| 6 Human intrusions & disturbance | Unknown | |||

| 7 Natural system modifications | Unknown | |||

| 9 Pollution | Unknown | |||

| 11 Climate change & severe weather | Unknown |

Conservation activities

The Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) has embarked on a number of conservation initiatives. For example, JGI worked with local communities to create a land use plan for their villages (Langat 2019). JGI created the Lake Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation and Education (TACARE) program in 1994, which aims to support sustainable livelihoods in the local communities while halting forest degradation. The program focuses on socio-economic development and sustainable natural resource management. Efforts to monitor health systematically at the site began in 2000. Observers conducting local follows every day take note of clinical signs (e.g., coughing, diarrhoea, wounds), both for the target of their follow, and for any individual observed ill (Wilson et al. 2020).

Table 4. Conservation activities reported for Gombe National Park

| Category | Specific activity | Description | Implementing organization(s) | Year of activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Species health | 3.1 Wear face-masks to avoid transmission of viral and bacterial diseases to primates | Since 2017 observers are required to wear face masks when with chimpanzees (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) | |

| 3 Species health | 3.2 Keep safety distance to habituated apes | A minimum distance of 7.5 m is maintained for researchers, and 10 m for tourists, who are more likely to carry respiratory viruses due to recent travel (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) | |

| 3 Species health | 3.3 Limit time that researchers/tourists are allowed to spend with habituated apes | Tourist visits are restricted to no longer than one hour, and in groups no larger than six people (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) | |

| 3 Species health | 3.4 Implement quarantine for people arriving at, and leaving the site | Visiting researchers are asked to complete a 7-day quarantine before following chimpanzees (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) | |

| 3 Species health | 3.11 Implement continuous health monitoring/permanent vet on site | JGI employs a full-time research team at Gombe, including a vet (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) | |

| 3 Species health | 3.13 Implement a health programme for local communities | The health monitoring project at the site has expanded to include a “One Health” approach, integrating diagnostic surveillance for chimpanzees and baboons, and examining links with people and domesticated animals (Wilson et al. 2020). | Ongoing (2020) | |

| 4 Education & awareness | 4.1 Educate local communities about apes and sustainable use | Awareness raising among school children conducted by the Gombe Stream Research Centre. For example, students grow seedlings at school and transplant them back in their homes under the village reserve program (Langat 2019). | Ongoing (2019) | |

| 5 Protection & restoration | 5.2 Legally protect ape habitat | The site is designated as a National Park. | Ongoing (2021) | |

| 8 Permanent presence | 8.1 Run research project and ensure permanent human presence at site | Long-term research at the site has provided benefits to wildlife conservation, for example, by understanding disease patterns and requirements for ecological monitoring, habitat use and connectivity, and engagement of local communities in research and conservation (TAWIRI 2018). | Ongoing (2018) |

Conservation activities list (Junker et al. 2017)

Challenges

Table 5. Challenges reported for Gombe National Park

| Challenges | Specific challenges | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not reported |

Enablers

Table 6. Enablers reported for Gombe National Park

| Enablers | Specific enablers | Source | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Site management | |||

| 2 Resources and capacity | |||

| 3 Engaged community | |||

| 4 Institutional support | |||

| 5 Ecological context | |||

| 6 Safety and stability |

Research activities

Jane Goodall began habituating the Kasekela community in the 1960s, and demographic records have been continuously kept ever since (Weiss et al. 2017). From 1963 to 2000, chimpanzees were provisioned with bananas at an artificial feeding station, with daily records made of their behavior. Since the early 1970s, field assistants have conducted dawn-to-dusk focal follows of the chimpanzees everyday throughout their range (Weiss et al. 2017). In November of 1960, Goodall observed that chimpanzees make and use tools. This discovery revolutionized the field of animal behavior; up until then it had been presumed that only humans could construct and use tools (JGI).

Documented behaviours

Table 7. Behaviours documented for Gombe National Park

| Behavior | Source |

|---|---|

| Investigatory probe | Goodall 1968 |

| Play-start | Goodall 1968 |

| Leaf-sponge | Goodall 1964 |

| Branch-shake | Goodall 1968 |

| Container: Leaves used to catch/hold material | Goodall 1968 |

| Leaf-brush: Leaves used to brush bees, etc. away from an entrance or surface | Goodall 1986 |

| Food-pound onto wood: Food item smashed open by beating it on a hard wooden surface, like the base of a tree | Goodall 1968 |

| Food-pound onto other: Food item smashed open by beating it on a surface other than wood, such as stone or hard earth | Goodall 1968 |

| Termite-fishing using leaf midrib | Goodall 1964 |

| Termite-fishing using non-leaf materials: Probing instrument, sometimes modified, used to extract termites from tunnels | Goodall 1964 |

| Lever open: Stout stick is used in levering fashion to enlarge insect or bird nest | Goodall 1968 |

| Self-tickle: An object is used to probe ticklish areas on self | Goodall 1986 |

| Aimed-throw: Throwing of object with clear (even if inaccurate) tendency to aim | Goodall 1964 |

| Leaf-napkin: Leaves used to clean body surfaces | Goodall 1964 |

| Leaf-groom: ‘ Grooming’ of leave | Goodall 1986 |

Exposure to climate change impacts

External links

Relevant datasets

References

Goodall, J. (1963). Feeding behaviour of wild chimpanzees. A preliminary report. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London 10:39–47.

Goodall, J. (1964). Tool-using and aimed throwing in a community of free-living chimpanzees. Nature 201:1264–1266.

Goodall, J. (1968). The behaviour of free-living chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve. Anim. Behav. Mon. 1, p. 161-311.

Goodall, J. (1986). The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of behaviour. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Langat, A. (2019, February 28). For the famed chimps of Gombe, human encroachment takes a toll. Mongabay. Online: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/02/for-the-famed-chimps-of-gombe-human-encroachment-takes-a-toll/

Lonsdorf, E. V., Travis, D. A., Raphael, J., Kamenya, S., Lipende, I., Mwacha, D., ... & Gillespie, T. R. (2021). The Gombe Ecosystem Health Project: 16 years of program evolution and lessons learned. American journal of primatology, e23300. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23300

Pusey, A. E., Pintea, L., Wilson, M. L., Kamenya, S., & Goodall, J. (2007). The contribution of long‐term research at Gombe National Park to chimpanzee conservation. Conservation Biology, 21(3), 623-634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00704.x

Weiss, A., Wilson, M. L., Collins, D. A., Mjungu, D., Kamenya, S., Foerster, S., & Pusey, A. E. (2017). Personality in the chimpanzees of Gombe National Park. Scientific data, 4(1), 1-18.https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.146

Wilson, M. L., Lonsdorf, E. V., Mjungu, D. C., Kamenya, S., Kimaro, E. W., Collins, D. A., ... & Goodall, J. (2020). Research and conservation in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem: Challenges and opportunities. Biological Conservation, 252, 108853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108853

Page created by: A.P.E.S. Wiki team Date: NA