Difference between revisions of "Western chimpanzee"

| Line 165: | Line 165: | ||

Kormos R and Boesch C 2003. Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of Chimpanzees in West Africa. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group and Conservation International, Washington DC, USA <br> | Kormos R and Boesch C 2003. Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of Chimpanzees in West Africa. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group and Conservation International, Washington DC, USA <br> | ||

Kühl HS et al 2017. The Critically Endangered western chimpanzee declines by 80%. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajp.22681 American Journal of Primatology. 79 e22681] <br> | Kühl HS et al 2017. The Critically Endangered western chimpanzee declines by 80%. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajp.22681 American Journal of Primatology. 79 e22681] <br> | ||

| − | IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group. (2020). Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of Western Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) 2020–2030. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. <br> | + | IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group. (2020). Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of Western Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) 2020–2030. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. [https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2020.SSC-RAP.2.en Online] <br> |

Junker J et al 2012. Recent decline in suitable environmental conditions for African great apes. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ddi.12005 Diversity and Distributions] 18:1077–91. <br> | Junker J et al 2012. Recent decline in suitable environmental conditions for African great apes. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ddi.12005 Diversity and Distributions] 18:1077–91. <br> | ||

Junker J et al. 2017. Primate Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Interventions. University of Cambridge, Cambridge. [https://www.conservationevidence.com/synopsis/index Online]<br> | Junker J et al. 2017. Primate Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Interventions. University of Cambridge, Cambridge. [https://www.conservationevidence.com/synopsis/index Online]<br> | ||

Revision as of 02:41, 7 July 2020

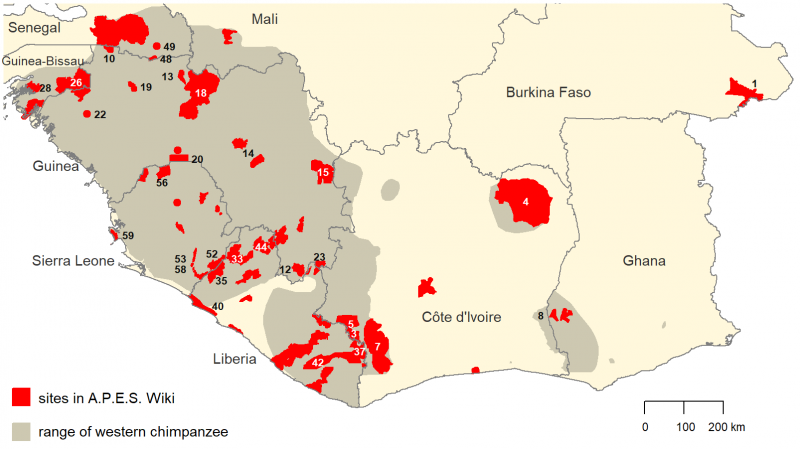

Western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) are a subspecies of chimpanzees that occur in eight West African countries: Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Republic of Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Senegal and Sierra Leone. They are thought to be extirpated from Benin, Burkina Faso, Gambia and Togo (Ginn et al. 2013, Campbell and Houngbedji 2015, Humle et al. 2016).

In 2020, the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group published a new conservation action plan that comprehensively reviews the status, threats, and priority conservation strategies and actions for western chimpanzees (online). The 2020-2030 Action Plan provides an update from the previous regional conservation action plan for chimpanzees in West Africa (Kormos & Boesch 2003), and elaborates significantly upon how stakeholders can address both direct as well as indirect threats to chimpanzees.

Western chimpanzees occur in a diversity of habitats from rainforests to savanna-dominated areas, and their behavioural flexibility enables them to also survive in agricultural areas with remnants of forests (Boesch & Boesch-Achermann 2000, Hockings et al. 2015, Pruetz & Bertolani 2009; van Leeuwen et al. 2020; Wessling et al. 2018).

Across different sites in West Africa, chimpanzees have been observed to use tools to access certain foods such as cracking nuts (e.g., Bossou, Taï National Park), fishing for algae (e.g., Moyen-Bafing National Park), extracting honey (e.g., Boé), or hunting (e.g., Fongoli). Additional interesting behaviors only observed in the region include accumulative stone-throwing at Boé, and Sangaredi, and crab-fishing at Seringbara. In very hot and arid climates chimpanzees have been observed to use caves (e.g., Fongoli, Bafing, Dindefelo).

Threats

Western chimpanzees are threatened by habitat destruction and fragmentation, illegal hunting and diseases IUCN Red List assessment. Human activities driving these threats differ between sites, also because ecological, economic and social conditions differ greatly. Contributors to habitat loss in the region include both small-scale (subsistence agriculture, artisanal logging, artisanal mining) and large-scale (infrastructural development, mining and other industrial extraction). While poaching and agricultural activities have been reported for most western chimpanzee sites, fires causing habitat destruction are, for example, mostly a concern in savanna-dominated areas (e.g., northern Guinea, northern Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau and Senegal).

Western chimpanzee populations have declined by 80% between 1990 to 2014 (Kühl et al. 2017) and consequently, this subspecies was uplisted to Critically Endangered during the most recent IUCN Red List assessment (Humle et al. 2016). Based on range-wide species distribution modelling, it has been estimated that approximately 52,800 individuals remain (Heinicke et al. 2019).

Conservation

Most commonly implemented activities for the protection of western chimpanzees include legally protecting their habitat, environmental education activities, and anti-poaching patrols. As only 8% of western chimpanzees occur in high-level protected areas (e.g., National Parks, Heinicke et al. 2019), conservation activities increasingly focus on chimpanzee protection outside of protected areas, for example, by supporting more effective farming to spare encroachment of natural land, or by providing benefits to communities for sustainably managing forests. To care for chimpanzee confiscated from the illegal wildlife trade sanctuaries have been established at Haut Niger National Park, Western Area Peninsula National Park and in Liberia. Effectiveness of conservation interventions was reviewed as part of the Conservation Evidence Project in Junker et al. (2017) including several western chimpanzee sites.

The 2020 Conservation Action Plan (online) stressed the need for the establishment of best practice for implementing conservation activities, but also improved regional coordination and challenges in financing conservation (IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group 2020).

In many regions, humans and chimpanzees have been living in close proximity for centuries, but the continuing destruction of chimpanzee habitat has led to an increase in conflicts. The IUCN Primate Specialist Group Section for Human Primate Interactions was founded recently to pool practical and academic expertise on interactions between humans and primates.

Research

Research on western chimpanzees has been ongoing for several decades, especially at the long-term research sites of Bossou and Taï National Park. Research sites have been established to study chimpanzees also outside of rainforest habitat, for example, Boé, Cantanhez National Park, Comoé National Park, Dindefelo, and Fongoli. Increasingly, chimpanzees are also studied in human-modified landscapes, for example, at Cantanhez National Park, and across Sierra Leone.

Chimpanzee ecology and behaviour are not only studied at the above mentioned long-term research sites but, for example, also at Gola Rainforest National Park, Haut Niger National Park, Moyen-Bafing National Park, and Seringbara.

Additionally, there are a few but growing number of projects which involve multiple sites within West Africa, most notably the PanAfrican Programme. The Pan African Programme: The Cultured Chimpanzee (PanAf) aims to better understand the evolutionary and ecological drivers of the large diversity in behaviours across chimpanzee populations, for which data have been collected in at least 18 western chimpanzee sites (of which 15 are available on the Wiki). Wessling et al. (2019) additionally collected data across multiple sites in Senegal, whereas multiple scholars are beginning to develop collaborations from which multiple West African sites can be compared (e.g. Sugiyama 1995; Wessling et al. 2018; Schoening et al. 2008).

Data from western chimpanzee sites was also used for modelling suitable environmental conditions for apes across Africa (Junker et al. 2012).

Sites included in A.P.E.S. Wiki

References

Campbell G and Houngbedji M. 2015. Conservation status of the West African chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) in Togo and Benin. Arlington, VA: Primate Action Fund. Unpublished report.

Ginn LP et al 2013. Strong evidence that the West African chimpanzee is extirpated from Burkina Faso. Oryx 47, 325–6.

Heinicke S et al 2019. Advancing conservation planning for western chimpanzees using IUCN SSC A.P.E.S.–the case of a taxon-specific database. Environmental Research Letters 14: 064001.

Hockings KJ et al 2015. Apes in the Anthropocene: flexibility and survival. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 30, 215–222.

Humle T et al 2016. Pan Troglodytes ssp. verus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. Online: iucnredlist.org

Kormos R and Boesch C 2003. Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of Chimpanzees in West Africa. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group and Conservation International, Washington DC, USA

Kühl HS et al 2017. The Critically Endangered western chimpanzee declines by 80%. American Journal of Primatology. 79 e22681

IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group. (2020). Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of Western Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) 2020–2030. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. Online

Junker J et al 2012. Recent decline in suitable environmental conditions for African great apes. Diversity and Distributions 18:1077–91.

Junker J et al. 2017. Primate Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Interventions. University of Cambridge, Cambridge. Online

Pruetz, J and Bertolani P 2009. Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) behavioral responses to stresses associated with living in a savannahmosaic environment: Implications for hominin adaptations to open habitats. PaleoAnthropology 2009, 252–262.

Schöning C et al. 2008 The nature of culture: Technological variation in chimpanzee predation on army ants revisited. Journal of Human Evolution 55(1): 48-59.

Sugiyama Y. 1995. Tool-use for catching ants by chimpanzees at Bossou and Monts Nimba, West Africa. Primates 36: 193-205.

Wessling EG et al. 2018. Seasonal variation in physiology challenges the notion of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) as a forest-adapted species. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 6:60.

Wessling EG et al. 2019. Stable isotope variation in savanna chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus ) indicate avoidance of energetic challenges through dietary compensation at the limits of the range. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 168 (4), 665-675.